I’ve a sneaking suspicion that the second “I” in “Tidings” was actually a lower case “L”.

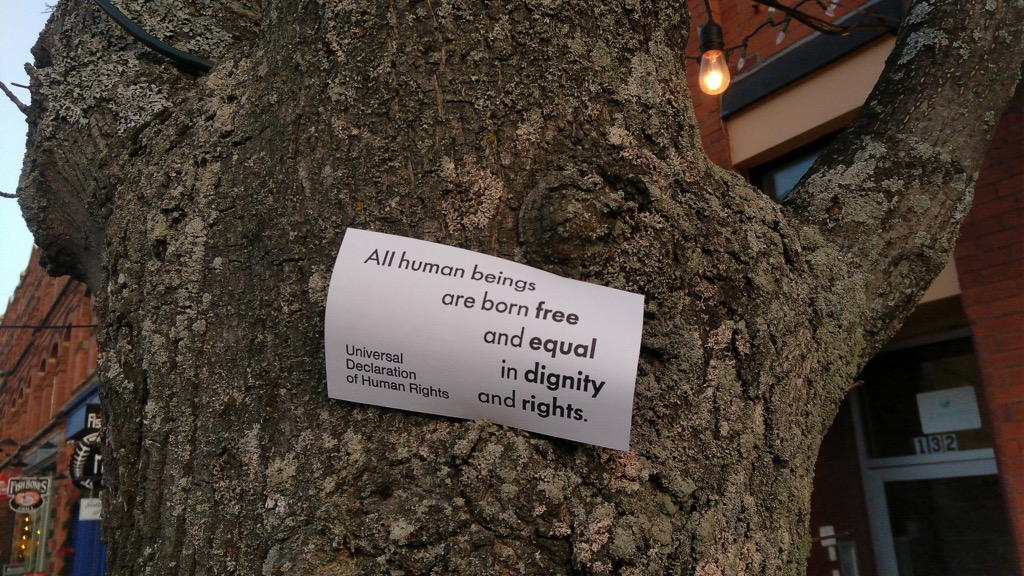

December 10 is Human Rights Day and the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations.

I didn’t know this when I set and printed an index card with the first sentence of Article I; a fortuitous year, then.

To celebrate this day, there’s a panel discussion “Science as a Right” happening on Monday, December 10 from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. at the Beaconsfield Carriage House in Charlottetown. More details in The Buzz.

Seventeen days ago I reported a bug in the Bookmarks app for Nextcloud. Three days ago it got fixed, and today I installed the updated version.

The bug I reported concerned the way that tags are entered when the “bookmarklet” for the app is invoked: after every tag entry you had to click on the “tags” field to regain focus and enter another tag. This has now been fixed, as you can see in this short screencast that shows me entering several tags in rapid succession:

Sometimes submitting bug reports can feel akin to throwing bug reports into a black hole; it’s nice when this proves not to be the case.

This afternoon’s screening of California Typewriter went perfectly: we had a good mix of people, including friends of typewriter collector Martin Howard, who featured prominently in the film.

Last month my friend Catherine Hennessey gifted me an Olympia Monica Electric S; it had a stuck carriage return key that I’ve just this very minute managed to repair by adding some grease and moving around some fiddly springs. And so here is a short video of the sales report from the screening (with apologies for the shaky variable focus; the camera rig was sketchy and the auto-focus kept kicking in).

Keeping Some of the Lights On: Redefining Energy Security is a fascinating reexamination of what we mean by “energy security.”

Because demand and supply influence each other, we come to a counter-intuitive conclusion: to improve energy security, we need to make the power grid less reliable. This would encourage resilience and substitution, and thus make industrial societies less vulnerable to supply interruptions.

In other words, if it’s an issue that renewable sources of energy are intermittent, why not change the nature of the problem we’re seeking to solve.

I appreciate the pains that CBC editors took to make it clear that the CBC itself wasn’t accusing Dave Stewart of looking dumb in a hat.

The Third Session of the Sixty-fifth General Assembly wrapped up on Wednesday after 14 sitting days and I’ve written some code to do some statistical analysis of how the session went.

The code is rough and hacky, mostly because the Legislative Assembly’s Hansard is published only as mostly-unstructured PDF files; there’s just enough structure to ferret out who’s speaking and what they said, but the process is prone to error because there are just enough variations in the formatting that it cannot be relied upon to work 100% of the time.

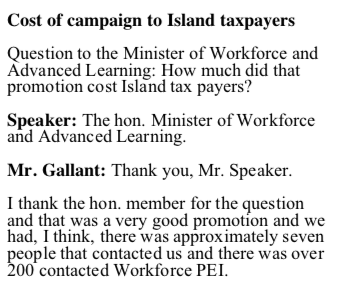

Look at this snippet from November 20, 2018, for example:

While the name of each person who speaks is rendered in bold in the PDF file, this doesn’t survive the conversion from PDF to text, so post-conversion I’m left with:

Cost of campaign to Island taxpayers

Question to the Minister of Workforce and

Advanced Learning: How much did that

promotion cost Island tax payers?

Speaker: The hon. Minister of Workforce

and Advanced Learning.

Mr. Gallant: Thank you, Mr. Speaker.

I thank the hon. member for the question

and that was a very good promotion and we

had, I think, there was approximately seven

people that contacted us and there was over

200 contacted Workforce PEI.

At this point I’m left to deduce the names of speakers by looking for patterns common to all, which boils down to something like “one or more capitalized words that start the line and are followed by a colon.” Which, in regular expression terms, looks like this:

/^(([A-Z][a-zA-Z\.\-]+\s?\b){1,4}):/

So in this brief excerpt this pulls out “Speaker” and “Mr. Gallant,” helpfully. But also, unhelpfully, “Advanced Learning,” which gets caught by the same pattern matching.

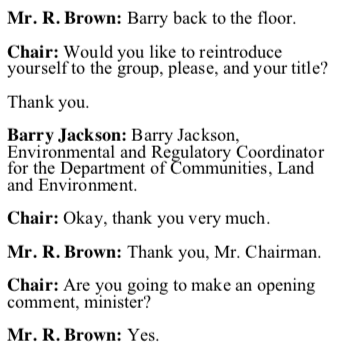

Things are further complicated by the presence of names in Hansard that are not Members of the Legislative Assembly or clerical staff, like “Barry Jackson,” here:

The pattern matching also misses things like “Leader of the Opposition” (“of the” not being capitalized).

That all said, it’s possible, even with these deficiencies, to get some rough, inaccurate-but-not-too-much-so statistical summaries from Hansard.

To start, I used a Python script I wrote a few years ago to harvest all of the Hansard PDFs on the Legislative Assembly website and convert them to text files (using pdftotext).

Next, for the heavy lifting, I processed the individual text files with a PHP script that used the aforementioned pattern matching to extract each person speaking, what they said, and the number of words spoken, along with the date, into a CSV file.

I limited the script to the 14 sittings days from this session, and ended up with a file hansard.csv. Each line of that file represents one speaker, so, from the above example, you’ll see this:

2018-11-20,"Thank you, Mr. Chairman.","Mr. R. Brown",4

2018-11-20,"Are you going to make an opening comment, minister?",Chair,9

There are 11,782 “utterances” like this in the file, which means that, give or take, 11,782 times over 14 days someone spoke in the Legislative Assembly on something.

Taking that CSV file into a spreadsheet and creating a pivot table by speaker and total number of words, and then hand-editing out the aberrations, I end up with 73 people speaking in total (with some duplication, as when a member is acting as Chair of Committee of the Whole House they appear as, for example, “Chair (Casey)”, not as “Ms. Casey”).

With that done, I can start to pull together some summary data.

Members of the Legislative Assembly

There were 398,088 words spoken by Members of the Legislative Assembly; broken down by speaker:

| Speaker | Words |

|---|---|

| Dr. Bevan-Baker | 42295 |

| Mr. J. Brown | 35995 |

| Mr. Trivers | 30231 |

| Mr. Myers | 27950 |

| Premier MacLauchlan | 25204 |

| Ms. Biggar | 23902 |

| Mr. R. Brown | 23573 |

| Ms. Bell | 22039 |

| Mr. Mitchell | 20553 |

| Mr. Fox | 19759 |

| Leader of the Opposition | 17771 |

| Mr. MacDonald | 16293 |

| Mr. MacEwen | 12176 |

| Mr. Palmer | 10130 |

| Mr. Gallant | 9419 |

| Mr. Roach | 8744 |

| Ms. Mundy | 8082 |

| Mr. LaVie | 7502 |

| Ms. Compton | 7294 |

| Ms. Casey | 5772 |

| Mr. McIsaac | 5659 |

| Mr. Henderson | 4926 |

| Mr. MacKay | 4701 |

| Mr. Dumville | 3960 |

| Mr. Perry | 2755 |

| Mr. Murphy | 1403 |

Strangers

A total of 24 people were invited onto the floor as “strangers”–including me!–this session, speaking a total of 29,040 words. By stranger:

| Speaker | Words |

|---|---|

| Rona Ambrose | 4777 |

| Dave Pizio | 2795 |

| Clare Henderson | 2645 |

| Peter Rukavina | 2636 |

| Graham Miner | 2087 |

| Barry Jackson | 2044 |

| Anne Partridge | 1696 |

| Blair Barbour | 1446 |

| Todd Dupuis | 1201 |

| Nichola Hewitt | 1114 |

| Curtis Toombs | 1086 |

| Kate Marshall | 809 |

| Jim Miles | 775 |

| Greg Wilson | 755 |

| Patricia McPhail | 553 |

| Scott Cudmore | 542 |

| Tim Garrity | 427 |

| Nigel Burns | 412 |

| Danny Miller | 379 |

| Nathan Hood | 347 |

| Dr. Wendy Verhoek-Oftedahl | 288 |

| Beth Gaudet | 200 |

| Gail MacPhee | 13 |

| Gary Demeulenaere | 13 |

Others

Others recorded in Hansard include the Speaker, the Clerk and Clerk Assistants, the Chairs of Committee of the Whole House, and the generic “An Hon. Member”:

| Speaker | Words |

|---|---|

| Chair | 19390 |

| Speaker | 18869 |

| Clerk | 2193 |

| Clerk Assistant | 1467 |

| Chair (Casey) | 1159 |

| Committee Clerk | 1008 |

| An Hon. Member | 820 |

| Some Hon. Members | 805 |

| Chair (McIsaac) | 645 |

| Clerk Assistant (Doiron) | 360 |

| Clerk Assistant (Reddin) | 183 |

| Chair (Perry) | 106 |

| Chair (Myers) | 84 |

| Chair (Trivers) | 80 |

| Chair (Fox) | 78 |

| Some Hon. Member | 2 |

An Hon. Member

When the identity of the member speaking cannot be discerned, “An Hon. Member” is credited. Stringing together these utterances makes for interesting found poetry; here’s an example:

Oh, great.

Yes.

That’s over.

Sure.

Hydrogen.

Could you table a copy?

It starts (Indistinct)

Call the hour.

No one is clapping for that one.

Oh.

Forget the facts.

Don’t confuse the (Indistinct)

There’s the truth.

Text Analysis

The excellent q utility allows SQL queries to be run on CSV files, allowing mentions of particular words or phrases to be counted. For example, here’s a query to count mentions of “Stars for Life,” the non-profit organization I sit on the board of:

q -H -d, "SELECT count(*) from ./hansard.csv where text like '%Stars for Life%'"

The result is 12. To find out who mentioned Stars for Life, I can do:

q -H -d, "SELECT speaker,count(*) as mentions from ./hansard.csv where text like '%Stars for Life%' group by speaker"

which produces:

Leader of the Opposition,1

Minister,1

Mr. MacEwen,2

Ms. Casey,4

Ms. Mundy,1

Peter Rukavina,2

Speaker,1

Donald Trump was invoked several times this session, and I can find out by who with:

q -H -d, "SELECT speaker,count(*) as mentions from ./hansard.csv where text like '%Trump%' group by speaker"

which produces:

An Hon. Member,1

Mr. R. Brown,3

To see what was said about Donald Trump:

q -H -d, "SELECT speaker,text as mentions from ./hansard.csv where text like '%Trump%'"

which results in:

Mr. R. Brown,"You’re (Indistinct), you’re like Donald Trump, you want to divide the Island and not unite the Island."

Mr. R. Brown,"Okay, Trump."

Mr. R. Brown,"You know what; 30 million litres of fuel have been saved. 90,000 tonnes of carbon have been taken out of the air; 90 ,000 tonnes have been taken out, 90,000 tonnes, 30,000 tandem loads of pollution have been taken out of the air from little old PEI. But no, do we hear thanks from the Green Party? No, Islanders are wrong. They then go on about the economy and you know, over the last couple of months there’s been a discussion going on about populism and populist leaders, polarizing things, we have it in Donald Trump, polarizing things. They’re going to give you great things and they’re going to do great things for you. We have the Green Party is saying: You have to put a carbon tax in, you have to tax – they’re sinners, you have to tax them –"

An Hon. Member,(Indistinct) Donald Trump.

Take It For a Ride Yourself

If you want to take this out for a ride yourself, here are the things you’ll need:

Where next?

To make this kind of analysis easier, having access to a version of Hansard where speakers and text are available as structured elements would be a big improvement.

For example, something like this:

<session date="2018-11-15">

<utterance>

<text>You’re (Indistinct), you’re like Donald Trump, you want to divide the Island and not unite the Island.</text>

<wordcount>19</wordcount>

<speaker>

<name>Mr. R. Brown</name>

<role>Minister of Communities, Land and Environment</role>

<speaker>

</utterance>

</session>

Other jurisdictions have moved in this direction, and I believe the Prince Edward Island is bound to have this capability eventually.

If you have any ideas about more accurate parsing of the Hansard PDF files, please let me know.

This morning’s project: this year’s Christmas card. More work to do for the reverse side, but I was happy with the way the JOY worked out.

The exoskeleton around Province House is finally getting its skin this week.

Twenty-five years ago, when Catherine and I moved to Prince Edward Island, our early experiences suggested that the Island was a magical place where almost every need could be met simply by asking around.

I arrived, for example, with a 1978 Ford F-100 pickup truck that I wanted to sell and replace with a car; within days of arriving I had it sold. And then replaced with a Nissan Sentra station wagon that also near-magically appeared at the right time.

When Catherine needed studio space, a chance conversation with Charlie, the superintendent of the building on Richmond Street where I was working, revealed that well-known lawyer Lester O’Donnell had just died. Lester had an office on the second floor of the building, a large 3-room suite overlooking the Basilica.

“Would you like to rent it?”, he asked.

Of course we did.

Catherine occupied this lovely, bright space from 1993 to 1995. We were living just a block away at 50 Great George Street in an apartment with no living room, so one of the rooms in the studio became our de facto living room: we’d go home for supper every night, and then come back to the studio to watch TV, read, and so on.

When we moved to Kingston, PEI in the summer of 1995, Catherine gave up the downtown studio and built one for herself in our back yard, a custom-designed 16 by 20 foot wooden building that’s still standing 20 years later. It served her well and, because she’d designed it herself, fit her needs like a glove. She worked there for 5 years, until pregnancy caused her to step back from art work for a while.

Fast forward 13 years: we’ve moved back to town, Oliver’s born, Oliver grows up, Oliver goes to school. Catherine’s back in the market for a studio. She laments the loss of the country studio. She laments the loss of the Lester O’Donnell studio. Then, one day, I’m walking down Richmond Street and I spot Ben Stahl, the artist who took over the studio from Catherine when she moved out in 1995: during our chat it became clear that Ben was in the process of getting ready to move out of the studio, with no heir apparent.

I ran home like the wind and found Catherine: “you’ve gotta phone Charlie: Ben’s moving out of the studio!”

And she did. That very day she made arrangements to move back into the studio more than a dozen years previous.

And she’s been a happy tenant for the decade since.

But now it’s time to move again: the Lester O’Donnell studio is on the second floor, and there are a lot of stairs involved in getting there, too many stairs for Catherine to reasonably manage these days.

Time for another chance conversation, this time with the Parish Administrator here at St. Paul’s Anglican: “there’s not any more space in the basement you’re looking to rent out, is there?”, I asked. As it happened, there was, and after some months of rearranging and cleaning and painting by dedicated church volunteers, the room directly across the hall from the Reinventorium was ready for her to move in this morning:

The movers were here for 3 hours, moving things down the block from the old studio, so that space is chock full of the tools of Catherine’s trade now. Lots of boxes to unpack. And the things she left behind to dispose of.

In addition to everything else, this move means that, for the first time in 27 years, Catherine’s work life and my work life will be cheek-by-jowl. We’ve always had our professional spaces and our home spaces; now, across the hall from each other at work, with our house directly across the street, the geography of our daily lives will become compressed into a circle with a diameter of 40 metres.

As I wrote to a friend earlier in the month, the prospect of this is equally terrifying and exciting.

Exciting because it means that we’ll see a lot more of each other than we have in a long time; what with being in love and all, that’s only good.

Terrifying because, well:

Catherine got a good introduction to the building this morning as her arrival coincided with a lunchtime Christmas decorating lunch for all the staff and tenants of the Parish Hall. Turkey soup, biscuits, partridge berry cake and fellowship. So far, the world colliding is going well.

I am

I am