Last Saturday I tweeted out a couple of screen shots showing the photo used in a CBC Prince Edward Island news story about a new Youth Advisory Council. The first showed the photo as it was used in the story itself, as it appeared in the CBC News mobile app on my phone:

The second screen shot showed how the same photo also appeared on a Dutch website advertising farewell gifts for employees:

I found the second example because the people in the photo the CBC used didn’t look familiar, and I was curious to know if they were actually “Island teens and youth” or not.

So I fed the first screen shot into the TinEye.com reverse image search and it led me to the original source of the image, a stock photo from the Shutterstock agency that has the title “People in our company get on together very well.”

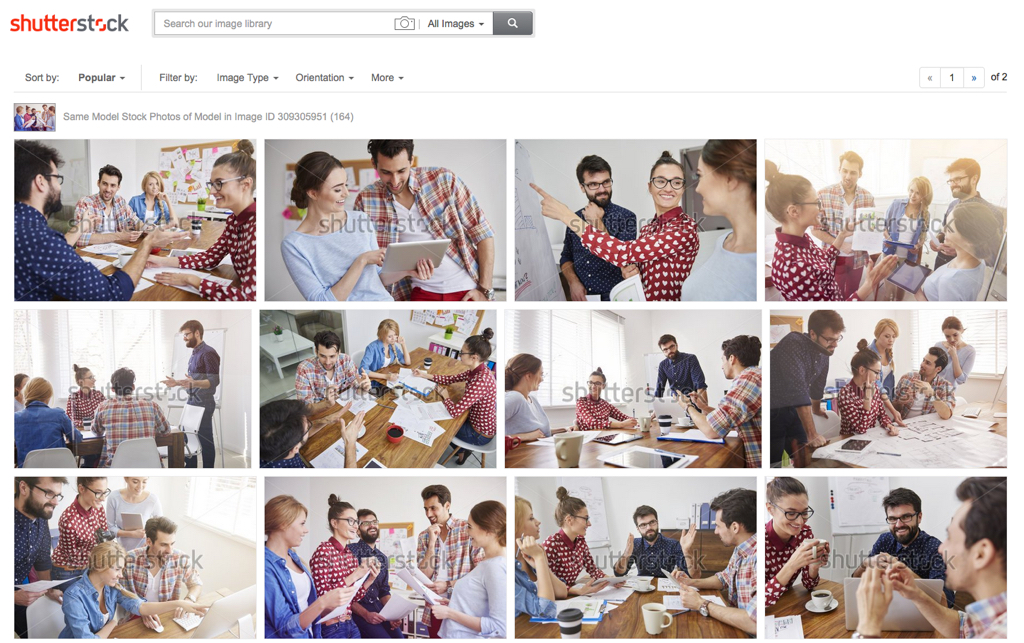

On the same Shutterstock page you can find the same models engaged in all manner of other activities, from Great team is basic of success in business to Interesting idea of my colleague:

The next day, CBC broadcaster (and friend) Karen Mair commented on Twitter “wish I understood the gravity of your posts.”

A valid question for her to raise: was I merely being “gotcha!” flippant in my tweet, or is there something I’m really concerned about?

There is something I’m really concerned about.

CBC News is in the truth business; it says so right in its Journalistic Standards and Practices (emphasis mine):

We seek out the truth in all matters of public interest. We invest our time and our skills to learn, understand and clearly explain the facts to our audience. The production techniques we use serve to present the content in a clear and accessible manner.

What bothers me about the use of stock photography is that it isn’t the truth.

The five people pictured above the headline “Teens and young adults can apply to new youth advisory council” are, in fact, not real people in a position to do this: they are paid models, acting in generic scenes.

Photography is journalism just as much as words are, and in the same way that it would be unacceptable for a CBC journalist to pull generic text from a generic text agency, it’s simply disingenuous to illustrate a news story with generic photos of generic people who are not, in fact, the subject of the story.

When I consume reporting from CBC News, whether it’s online, on the radio, or on television, I want to be able to rely on the veracity of what I’m reading or hearing or watching. I don’t want to have to wonder “is that a photo of a real car accident, or one they pulled off a stock photo site?”

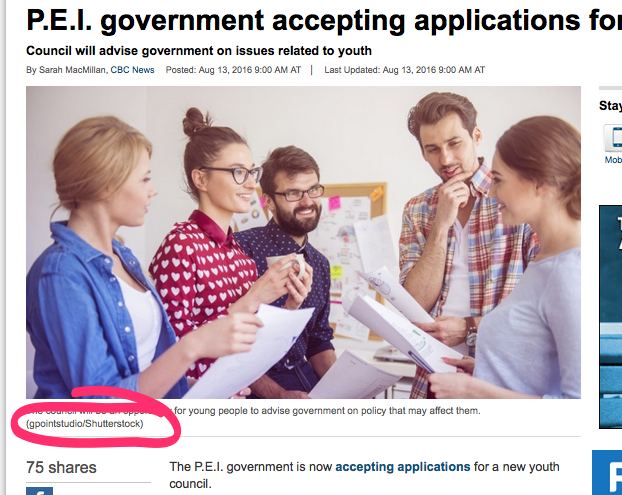

The fact that a stock photo was used was disclosed, both on the mobile app (if you tap on the info icon over the photo) and on the web, in the photo credit:

But this isn’t, for me, a question of disclosure-or-not, it’s a question of the proper role of illustrative photography in CBC journalism.

The same Journalistic Standards and Practices document has a section on Production Principles that touches more closely on this use of generic or simulated media:

A reenactment of an event must match the reality as closely as possible. When a reenactment is necessary for a proper understanding of the subject, we take care to be factually accurate, using transcriptions, minutes or official documents. We may use a transcript word for word or set the reenactment in the location where the actual scene occurred. To eliminate any risk that the audience will confuse the reenactment with the reality, we will ensure that the audience can clearly identify the reenacted scenes.

Other methods of illustrating a subject may attempt to describe a situation in general terms without pretending to be a precisely accurate rendering of reality. Such methods can be used, subject to certain conditions.

A simulated scene aims to evoke or give an impression of an event, its protagonists, their actions and the place where the event occurred. A simulated scene is produced and presented in a way that makes clear it is an evocation rather than a precise depiction of reality. If a risk of confusion remains, we advise the audience that the scene is simulated not real.

Generic scenes are commonly used in audiovisual production. These are often everyday actions like walking, answering the phone, looking at a document, closing a door. These scenes clearly serve as general illustration and in no way pretend to describe real facts precisely.

I don’t think the use of generic stock agency models standing in for real Prince Edward Island teens and young adults meets this standard: these models are not a reasonable facsimile of Island teens and young adults, their inclusion is not an accurate depiction of what the Youth Advisory Council will look like or how it will operate (which is largely unknown at this point), and its inclusion is not necessary for the proper understanding of the story.

Although the use of a stock photo is disclosed in the photo credit, the typical reader would, I hold, be left with the impression that this was a real photo taken on Prince Edward Island of something related to the new council.

In the end I propose a simple standard for the inclusion of photos in digital stories:

- Does the inclusion of the photo help tell the story?

- Is the photo a real photo of something actually related to the story?

Unless the answer to both questions is yes, leave the photo out.

Not a photo of me writing this blog post. Not a photo of me at all. Don’t know who it is. He could be playing music. He has a nice hat though.

(“Typing” by photographer Enric Fradera. Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license)

Comments

Agree 100%

Good posting, that photo of the writer in action at the end is the perfect ending!