The opening of a brand new Exploratorium yesterday in San Francisco got me thinking about its old home in the Palace of Fine Arts and a facsinating event that took place there 42 years ago this June.

In the Whole Earth Epilog, published in October 1974, Stewart Brand spins a long, rambling, and compelling tale of the “Whole Earth” enterprise over the previous three years, starting from the story of “Demise Party” in June 1971:

So, in June 1971, we had the Demise Party celebrating the self-termination of The Whole Earth Catalog, and all in all it was a rout. 1500 people showed up. The Exploratorium staff had their museum weirding around us at full steam. A band called The Golden Toad made every kind of music from bluegrass to bellydance. A non-stop non-score volleyball game competed for loudest activity with balloons full of inhalable laughing gas. And then at midnight Scott Beach announced from the stage that these here two hundred $100 dollar bills, yes, $20,000, were now the property of the party-goers. Just as soon as they could decide what to do with them.

The party was reported on in great detail for the Rolling Stone article “The Last Twelve Hours of the Whole Earth Catalog” (issue #86) which began:

The Demise of Whole Earth was a wake, and like any good wake it lasted until early morning, what with 1500 people haggling over the deceased’s estate.

The estate – a wad of 200 $100 bills – was a surprise “educational event” sprung by Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand on the former Whole Earth employees, contributors, and reviewers who had come to celebrate the publication of The Last Whole Earth Catalog. By the time of the party, June 12th, they had probably all digested an earlier education event, Brand’s decision a year and a half ago to stop publishing his successful Catalog this summer.

The $20,000, however, proved too much to deal in a single night, and by 8 AM the 1500 guests dwindled to 20. In the end the 20 delegated one of their number to hold the money, which itself had dwindled to $14,905, until they could reconvene to decide what to do with it. He stuffed the money into his jeans and drove off into the sunrise.

That article, by Thomas Albright and Charles Perry, was reprinted in early editions of The Seven Laws of Money (itself a compelling read).

Miraculously, there is video of the Demise Party; you can see it in this montage of news clippings and other Whole Earth material at about 23:20:

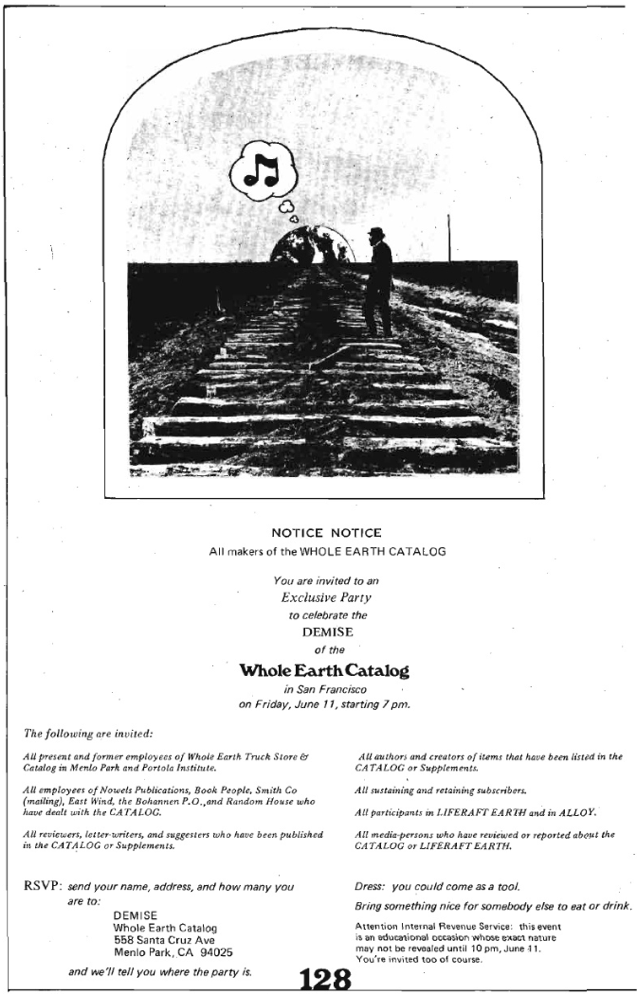

The invitation to the Demise Party appeared in the March 1971 Whole Earth Catalog supplement (conveniently available online):

Among those who attended was Richard Brautigan, as related here:

The evening had just gotten started (hosted by Scott Beech, music by The Golden Toad) when all the glitterati of S.F. started showing up, including Richard Brautigan and another man passing out a “free poem” entitled “Lichen.” I tried to get the two of them to autograph the poem, which was printed on legal-sized, greenish paper. Both refused. Instead of stamping the backs of hands (so people could come and go), we had these stacks of self-stick diffraction gratings from Edmund Scientific to put on people’s foreheads. Both refused.

In Stewart Brand’s own tale of the party and its aftermath, he goes on to relate the story of POINT Foundation and its mechanism for handing out grants (emphasis mine):

It was not a bad overture for the founding of POINT, the foundation that took over from Portola the dispensing of Whole Earth’s soon sizable income. Dick Raymond and I appointed a board consisting of ourselves, Huey Johnson from the Nature Conservancy, Mike Phillips from Glide Foundation, Jerry Mander (radical ad-man), and Bill English from Xerox. The seventh director was always a guest, called “Elijah,” different each time we met.

The first thing we did was give up on my “Mountain Fantasy” notion of a bifurcated high hard community — too pushily experimental. Instead we focussed on being a needle in the gaseous foundation world. We ruled that none of us could be with POINT more than three years. We dispensed (Jerry Mander’s brilliant stroke) with group decision about money — each director had $55,000 a year to give out at his unchallenged discretion. We funded quickly and without fuss, usually preferring to do without proposals and such. We held board meetings on salmon boats at sea, in tipis, in Glide’s sex room, at the Black Panther school in Oakland. And our grants were maybe no worse than other people’s — they’re listed in entirety in the Summer ‘74 Co-Evolution Quarterly if you’re interested.

Huey Johnson and Jerry Mander, who fought constantly, were the best funders. Dick Raymond and I were terrible. Now there’s mostly a new set of directors, whose qualities we shall see. The main lesson I learned was: it’s not enough to give money to someone who’s very good. They must also be in the grip of an overwhelming idea which is very good; otherwise a hideous paralysis will take them over and, in addition, freeze your friendship.

My parents owned copied of the Whole Earth Catalog, and I’ve accumulated my own collection over the years (to the point where I’ve had enough extra copies that I’ve been able to share them with fellow travellers); I was a Whole Earth Review subscriber in later years, and a Well member too. If there’s an underlying rhyme to my reason, its roots can likely be found somewhere in the Whole Earth enterprise, for which I owe Brand and his coconspirators a great debt.

Comments

Fantastic bit of Stewart Brand History – tickled to see him at ~26m30s ‘bopping’ a TV interviewer…thanks for pulling that together, Peter.