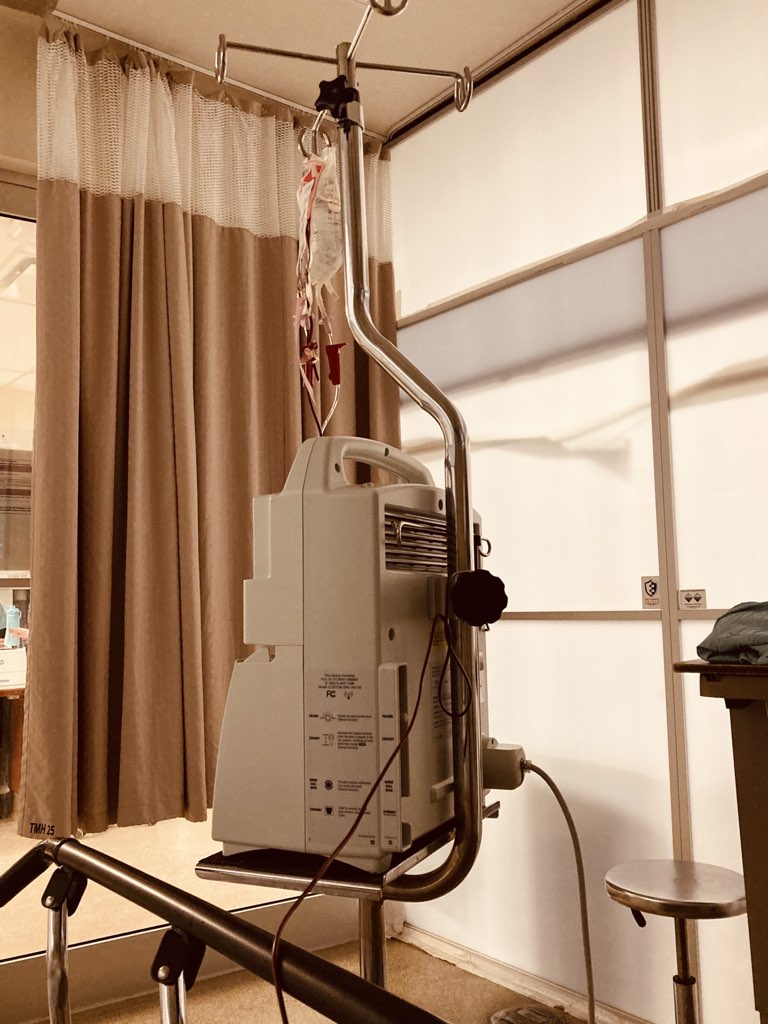

Eleven hours later, I would need two units of blood.

At the time, though, I was focused on the couple across from us in the Moncton ER waiting room. A casually-dressed couple in their 60s, obviously a couple for a long time, as they had a deft, wordless way of moving with each other, of communicating. They were there for him, it emerged: when the blood pressure trolley stopped at their seats, it was his blood pressure that was taken. I assumed their visit had something to do with his leg, as it was in a boot, strapped on with velcro, of the sort that people with a foot or ankle injury often wear.

Because not much goes on in the ER waiting room, I paid them a lot of attention. They shifted seats, got called in, got sent back out, ate snacks, played word games. I was confused by how his velcro-boot kept shifting from his right leg to his left leg. Eventually I realized it was simply because he was crossing and uncrossing his legs—the kind of thing you do a lot in the ER waiting room.

We’d gone over to Moncton for the weekend with Lisa’s parents, to an Airbnb on the outskirts, our Christmas gift to them. The rental was beautiful, a log cabin just enough out of the suburbs to feel rural and isolated, but within 10 minutes of the city proper. It was touch and go whether we’d go at all: I was still in the throes of a two week old chest cold, a cold that had consumed all of my energy and then some; I was exhausted. But, I reasoned, I wasn’t coughing so much, and I was certainly no longer contagious, so even if I was feeling 50%, I figured I might as well feel 50% in a log cabin as anywhere, with family, a hot tub, and wood-burning fireplace at the ready.

I was queasy the entire ride over, and increasingly feeling out of it, but soldiered on regardless. After an overnight in the cabin—a nice supper, a perhaps-foolhardy dip in the hot tub outside at -30ºC—it seemed clear, the next day, that I was getting worse, not better. By late-morning, I was feeling poorly enough that I phoned 811. After a 10-minute triage chat with a nurse, I was told to go to the ER.

And so, at 2:00 p.m., off we headed into the city, Lisa and I, confident that the posted wait times on the ER website of two to three hours would mean we’d be back for supper. At the time I thought I might have pneumonia, or some other chest-cold-gone-wild malady, and might receive antibiotics. Or maybe even just a “take it easy, son; you’ll be better soon.”

On arrival I was ushered into a triage booth and interviewed by a capable nurse. Between the two of us Lisa and I spilled out my symptoms: sick for two weeks, feeling better, then worse; feeling alternately dizzy, queasy, with an unrelenting cough. And, worst and most noticeable, feeling not altogether “there” most of the time. Almost as an aside, I also mentioned rectal bleeding that I’d been experiencing for a couple of weeks, seemingly due hemorrhoids, bleeding that I’d been reassuring Lisa was part of a regular and unconcerning pattern.

Just as we were finishing up, Lisa mentioned to the nurse that my colour had been off, that I sometimes looked pale, or yellow; the nurse agreed, noted that, and I watched her bump me up a triage level, which buoyed my spirits, as I assumed it meant I’d be seen earlier.

And then we waited.

The Moncton ER waiting room is like any ER waiting room anywhere: an unloved holding tank for indeterminately sick people, not unlike an airport waiting room for flights to unpopular destinations. There are two pay telephones, an almost-empty snack machine, a television mounted on the wall, playing only the weather forecast, two washrooms. It is the kind of place that takes your mental health as you arrive and downgrades it, simply from drearily waiting in a space that telegraphs you-don’t-really-matter-all-that-much.

Every hour or so the vitals cart came around to take my blood pressure. Because I had mentioned feeling dizzy, they took it twice every time, once sitting and once standing; orthostatic they called it. And there was a big difference between the two readings.

As the posted wait time came and went, we numbed ourselves to the idea that I’d be seen quickly. We entertained ourselves with Wordle. With snacks from the vending machine, with a failed attempt to order Lebanese food from Skip the Dishes (it simply never arrived) to a successful attempt to order submarine sandwiches from Door Dash. We charged our phones. I went for little walks. We talked, a lot. Lisa is, it turns out, a fantastic person to spend extended time in a waiting room with; as afternoon became evening became midnight, we never got grumpy, never turned on each other.

Finally, at 1:00 a.m., the velcro-boot couple were discharged and, 11 hours after arriving, my name was called. We were invited to walk through the big green doors, and taken into a curtained exam room.

It was only minutes before the doctor arrived, a rumpled man with an inquisitorial bedside manner that caught us unawares. We again spilled out my symptoms, and the doctor dutifully followed us down each path—chest cold, bleeding, colour, feeling out of it—sometimes asking questions that made us feel like we were in a duel. While there may have been—indeed, there was—method to his madness, it felt like an interrogation, especially after 2 weeks of illness, 24 hours of feeling out of it, and 11 hours of waiting room anticipation.

“We’ll get you taken care of,” he said on his way out.

Our confidence level was not great, and I think we each privately thought he’d written down “loopy couple; stick them somewhere, and then set them free.”

That didn’t happen.

Within minutes we were taken to another room around the corner, one with a throne-like recliner, with a step labelled “no step.” In short order I had many vials of blood drawn, and an ECG strapped to my chest. I was wheeled away for a head CT, and a chest X-ray, both of which happened without any wait at all. While I wasn’t panicking, I realized that we weren’t in ”take it easy, son; you’ll be better soon” territory any longer.

After a return from my visit to radiology, the doctor came back into the exam room.

“You’re anemic”, he announced. “Your hemoglobin is 70, and it should be more than 135. We’re going to need to give you a blood transfusion.”

It seems important at this point to stop and talk about rectal bleeding.

I never thought I’d write publicly about rectal bleeding. Or rectal anything, for that matter. Matters rectal are the undiscovered country of my literary non-fiction.

And yet here I am.

The reason I was in the Moncton ER needing a blood transfusion is directly related to that very same reticence.

Sure, I’d talked to my doctor about rectal bleeding before: it’s what led me to have a colonoscopy at age 36, as with a family history of colon cancer, it was a warning sign. That first colonoscopy didn’t show anything of concern, other than hemorrhoids. At that point, the power of “I don’t have colon cancer!!” was enough to take any attention I might have otherwise paid to the hemorrhoids.

In the intervening years, my hemorrhoids came and went, sometimes bleeding, sometimes not, and, using a not insignificant amount of magical thinking, I ignored them, mentioning them at annual checkups, but never pressing doctors about whether it was a concern or not, and them never saying “hold on, let’s talk more about your hemorrhoids.”

I was ashamed. I was squeamish. I was distracted. I feared whatever treatment might be offered me. Nobody wants to imagine scalpels and lasers in and around the bum.

A blood transfusion takes a long time; I didn’t know that. It started at 2:00 a.m., and I wasn’t released until 8:00 a.m. Lisa, bless her patient heart, was beside me throughout; we grabbed small snippets of sleep, but it was, for most intents and purposes, an all-nighter. There was a surreal quality to it all, knowing that anonymous donors were the source of the lifesaving something that was now dripping into me.

And then it was over.

We emerged into the bright Sunday morning Moncton sunshine, drove back to the cabin, had breakfast, went immediately to sleep. We drove home later the same day.

In the intervening weeks I’ve learned just how precarious having a hemoglobin level of 70 can be, had my blood and urine tested (hemoglobin up to 90, then, two weeks later, up to 123: a healthy trending up, but not yet optimal; all other metrics at “you’re in the prime of health” level—my nurse practitioner referred to my cholesterol level as “lovely”), I’ve had two iron infusions in the hospital here, plus a colonoscopy, ordered and delivered in record time.

The colonoscopy, absent the purgative prep, was a not unenjoyable experience that I watched on HDTV with fascination. The post-operative notes start “everything looked good,” and today I learned that the three polyps that were removed for analysis were ”tubular adenomas,” not cancerous but rather “the kind of thing that can become cancerous.” Good to have excised—a godsend, in fact, and a silver lining in all this—but, in the end, not the source of what ails me

The current working hypothesis: I have hemorrhoids. That bled. A lot. And I lost enough blood to make me anemic. I’ll go back to my surgeon toward the end of the month to talk about addressing that.

This has all been a chastening experience. For me, for Lisa, for Olivia, and for the circle of family and friends who surround us.

Any sense of embarrassment I once had talking about hemorrhoids has evaporated, now that they’re the talk of the town. This chastening, which I would have likely, at one point, kept entirely to myself, I’m now (sort of) okay writing about.

The sense of shame I have about neglecting my health, to the point of real peril, is something I’m still grappling with; I feel equal parts an idiot, and like I’ve had a lot going on for the last decade, so it’s okay to cut myself some slack.

I have struggled with this blog post; it’s been a draft for three weeks. At first the struggle was how frank to be; once I figured that out, I struggled to turn it into a life-lesson, to tie a neat bow, and come to a satisfying conclusion. But every path I wrote myself down ended up a dissatisfying blind alley; I searched in vain for life lessons, and, so far, have found none.

So I will end not with a life lesson, but with gratitude.

To everyone medical, from the irascible Moncton ER doc, to my nurse practitioner, to my colonoscopy surgeon, to the myriad nurses who’ve drawn blood, and taken my blood pressure, and served me warm blankets.

To my friends and family, who’ve worried about me, asked after me, offered kind words and practical support.

To Olivia, who’s been through too much, and who feared I’d die before my birthday.

To Lisa, who’s loved me all the way through this: she’s managed our household solo while I’ve been down, fed me from vending machines, driven me to appointments, held my hand. She’s bravely jumped into a remarkable pool of vulnerability with me that continues to take my breath away.

And perhaps there is a neat bow to tie this up with: I am so, so happy to be alive.

I am

I am

Comments

I am so happy you are alive,

I am so happy you are alive, too! Continue to feel better and better.

Full of gratitude, here, too.

Full of gratitude, here, too.

And: Thanks for your level of frankness.

<3

<3

Your writing is so compelling

Your writing is so compelling, thanks for sharing it with us. I’m glad you are on the mend ❤️🩹

Sorry to read about all your

Sorry to read about all your troubles and glad you have it sorted out. Take care.

Oh Peter- you are so generous

Oh Peter- you are so generous in your sharing and educating of others. Allowing yourself to be so vulnerable and always so thoughtful. We are so glad that you are ALIVE and in our lives! xo

"Fear & Healing in New

"Fear & Healing in New Brunswick". What a fine description of the E.R. (endless retardation?) experience! Thanks for 'writing publicly about rectal bleeding'. I never thought I would be reading about the subject with any interest, but giving more exposure to the haemorrhoid (or anything) as a life-threatening scourge seems like a sure-fire way to pique interest. Of course, I'm glad to know that you are recovering your health. Part of the reason I took the time to read your blog post is that I have more discretionary time than usual. I have been feeling unwell and drained of energy since Wednesday yet the last thing I want to do is engage with medics. I would take the hot tub under the stars over the plastic chair beneath the neon no matter what...so your account offers an opportunity for reflection and insight. And no matter how ill I become, I seem to remain a compulsive proofreader; there may be a missing "to" in: 'once I figured that out, I struggled turn it into a life-lesson'. Sending healing love from the riverbank on this sunny Saturday morning. :-)

What an ordeal!

What an ordeal!

I sure hope to see you soon. It’s funny how stories like this happen and they are seldom shared. I’m sure your sharing gives others courage. Wishing you the best

Thanks for sharing, Peter.

Thanks for sharing, Peter. Such a scary experience for all of you. I am glad that things are improving.

Wow, scary. Glad things

Wow, scary. Glad things turned out ok! Eleven hours waiting in ER, can't imagine the tedium icw worry.

Good grief, Peter, that was a

Good grief, Peter, that was a close one! I'm glad you're through it and yes, thank heaven for those who love us.

Glad you are recovered and

Glad you are recovered and wish you well!

A salutary lesson, which I

A salutary lesson, which I thank you for writing. Very glad to hear you are on the mend.

Thanks for the story - happy

Thanks for the story - happy to hear you're on the mend!

Thanks for sharing this Peter

Thanks for sharing this Peter. Not an easy story to tell, but so important for us to be aware of; your wonderful storytelling skills shine once again. Great to hear you are on the mend.

A powerful story, beautifully

A powerful story, beautifully told from the heart. ALL of us readers/friends are thankful that you took care of yourself. And, I appreciate the bravery and honesty with which you share (always). Thank you, Peter.

Peter, thank you so much for

Peter, thank you so much for you candor. It is not a topic any of us delight in and yet it is something so many may experience. Your sharing is much appreciated and I sure hope healing continues to full strength…!

Add new comment