Yesterday I saw this tweet, about a teach-yourself-Norwegian audiobook available from the Public Library Service:

As I do want to learn Norwegian, at least in theory, I followed the link, which led me to a page on the Prince Edward Island-branded Overdrive.com website. To “borrow” this audiobook I needed to enter my library card number, put the audiobook in my “cart” (thus starting us, forebodingly, down the road toward ecommerce language), then “checkout” (ibid), select a 7, 14 or 21 day “lending period,” download a XML wrapper file for the audiobook, download the “Overdrive Media Console” software for my Mac, and then open the XML wrapper inside the Media Console to actually download what, in the end, was simply 3 non-DRMed MP3 files.

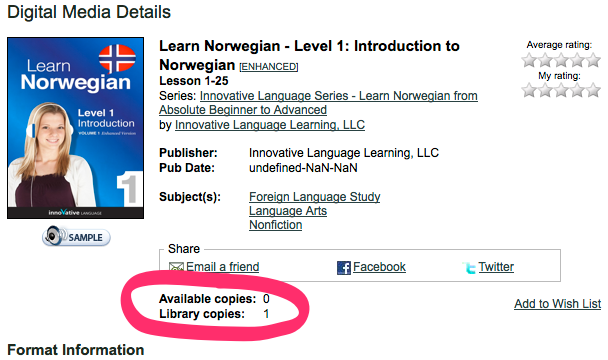

After listening to the first 5 minutes of the first MP3 file, I decided that I didn’t really have any interest at all in learning Norwegian, so I tried to “return” the audiobook, but found no way to do so. Apparently there isn’t one, at least in the Mac version of the Media Console. So not only am I stuck with this MP3 file for the next 21 days (I’m only allowed 10 digital “loans” at a time), but, worse yet, nobody else in Prince Edward Island can learn Norwegian for the next 21 days because there are, as you can see in the screen shot from Overdrive’s website below, “Available copies: 0.” Because of me.

As near as I have been able to determine, I may be the only person who thinks this is an absolutely crazy system for the public library-mediated circulation of digital objects.

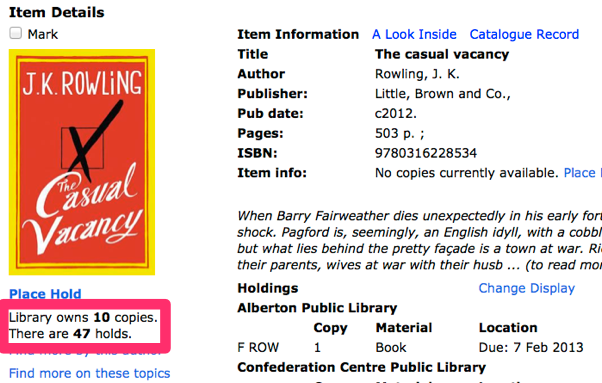

Libraries have hundreds of years of experience in managing the circulation of physical objects, and one of the defining characteristics of physical objects is that there are only so many of them to go around. And so, for example, there only 10 copies of The Casual Vacancy in the library system and 47 people who want to read it:

But Learn Norwegian - Level 1: Introduction to Norwegian, being simply a collection of MP3 files, isn’t shackled to this physical reality: there can be an infinite number copies of these MP3 files created so that, in theory, should the Premier decide that everyone in PEI should learn Norwegian, it would be trivial to pass a copy out to every citizen.

And yet, for some reason, we’ve opted to acquiesce to a system that takes the regular old model we’re all used to for managing and circulating physical objects and, absurdly, applies it to digital objects. So I’ve now “checked out” the Norwegian book for the next 21 days (even though, in truth, I’ve deleted all trace of the MP3 files from my computer).

I’m not arguing against digital rights management here (I’ll argue about that elsewhere; it too is crazy, but a harder crazy to fight): it’s worth noting that the MP3 files that I am technically “borrowing” right now have no restriction on copying them. While it would likely be a contravention of the terms I agreed to at some point in the process, there’s no technical reason why I couldn’t be running off copies for every Islander right now. Indeed there’s no technical reason that, despite the Overdrive Media Console’s insistence to the contrary (“All copies of this title, including those transferred to portable devices and other media, must be deleted/destroyed upon expiration.”), I couldn’t hang on to the MP3 files for the rest of my life.

So what I have “borrowed,” then, is really just a flag in an Overdrive database that says, in essence, “don’t let anyone else in Prince Edward Island learn Norwegian for the next 21 days.”

This is crazy, and we must demand better, more rational systems from our library, if only because we’re making up systems and processes here that will be with us for generations.

I am

I am

Comments

Rest assured that you are

Rest assured that you are *not* the only person who thinks this is an absolutely crazy system for the public library-mediated circulation of digital objects.

That said, I just had to drag some fish into a cartoon ocean to prove I was a human in order to submit this comment.

Now that I’m finished with this content form, someone else can use it!

No, you are not the only one

No, you are not the only one who thinks this is an absolutely crazy system for the public library-mediated circulation of digital objects. Public library staff find it crazy, too! In fact, when my library talked with an OverDrive representative, that was one of our questions: why can’t someone return an ebook when they are done with it? I don’t think we got a satisfactory answer, and we did not sign with OverDrive (for many reasons).

Other companies are at least working on that issue. I believe Axis 360, the ebook delivery system from Baker & Taylor, either has or is working on that option, to return a book when the borrower is finished with it.

Libraries have no problem with the one-copy-one-user foundation. But we need the assistance of the companies to allow us to treat ebooks like pbooks. Most publishers don’t like that idea, as they treat ebooks like software that is licensed rather than books that are purchased. Again, little libraries can do on their own about that. Bigger, better-funded libraries are trying to fight back, like Douglas County Library, but many of us don’t have those options right now.

Thanks for your thoughts on

Thanks for your thoughts on this, Becki.

I think libraries do have an option here: regional and national library organizations can use collective bargaining power to approach publishers (more) as equals than as customers. It’s only when the relationship is vendor-to-local-library-system that the deck is so much in favour of companies like Overdrive.

(Also, I think the “one copy one user” foundation needs looking at too, as it’s a vestige of the physical system that doesn’t, of necessity, need to be carried forward).

Heh, I came in here to say

Heh, I came in here to say what the other two comments have said. You are not alone, this is insanity to the core. Not just the issues you described, but also who the heck is Overdrive and why should they know what books—sorry, e-audio-books—you are checking out from your library? Anyway, I hope we can fix this one.

Well, yes, there’s another

Well, yes, there’s another thing. Take a look at Overdrive’s privacy policy and you’ll find things like this:

I’m pretty sure that this means that if I check out a digital copy of The Anarchist Cookbook from Overdrive that I’m not protected to the same degree as if I checked out a physical copy from my local library.

Speaking of which, maybe it’s time to interlibrary-loan a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook from the local public library to put that to a test.

Peter, I think you can return

Peter, I think you can return an ebook before it is due. Ask at your nearest public library - or email Liam at library headquarters. I think his email is on the library website…..Good luck, and let us know what you find out…..

<img alt=”” src=”http://media

<img alt=”” src=”http://media.ruk.ca/images//no…” style=”width: 531px; height: 91px;”/>

I’ve been using Overdrive for

I’ve been using Overdrive for about 5 years and have admittedly adapted to what I agree is an annoying system.

I think you nailed it with the comment that this is really a flag in a database. What it really is about is money for publishers. Publishers view libraries as advertisements that will hopefully lead to sales. Ebooks (both audio and written) are no different. Libraries are paying publishers a fee for this right that essentially means the book will be borrowed no more that 17 times per year. Really popular books with waiting lists in the dozens or hundreds will be purchased because people don’t want to wait for the new Dan Brown. So while the system bugs me, I think I understand it from the point of view of publishers/writers who are trying to make money from publishing and agree with their right to do so.

My main complaint is rather about selection. A couple of years ago one of the main publishers pulled all ebooks from libraries because they weren’t happy with the rights management. Not unhappy that it wasn’t easy enough to use but rather that they saw gaps in security. We need better solutions not only to make it easier for the reader to use but also so that its easier for the really good small publishers to use it and also enough security to make all of the big publishers happy.

You’re facing a

You’re facing a neurophysiological challenge too. I know of Swedish and I assume it’s true of the other Scandanivian languages too that they have vowel sounds we non-speakers can’t distinguish, and almost none of us can learn to distinguish them beyond the age of 10 or so.

Of course I agree with you

Of course I agree with you completely. Who would not? But since both publishers and libraries are on a one-way bus to Oblivion, this is a transient issue. In the interim, I look forward to more of your very amusing posts.

I heard you interviewed on

I heard you interviewed on Spark. I did not hear anyone on that program discuss how limitless access to library books would affect authors. Like everyone who works, authors expect to be paid for their hard work. If libraries can lend an ebook to as many people as request it, even though they have only bought one copy, there would be no need for anyone to buy any ebook, ever. Why should authors work for free? Do you? When an author self-publishes an ebook, they are requested to make it available to libraries, and the conditions you describe - that the library will lend out only the number of copies it has purchased at any one time - are carefully explained to the author. If this were not the case, no author would agree to have their book available in a virtual library. Yes, it makes sense to have the book available again when it has been returned. However, you advocated lending out multiple copies of an ebook when only one has been purchased. That would be piracy, and no author would agree to have their book in a virtual library under such circumstances.

You've latched onto a small

You've latched onto a small part of the entire conversation he is trying to engage. Imagine if their was a "return book" button readily available. This article never would have been written and someone else could borrow the book. This is more about the fact that the library doesn't actually have any control over Overdrive. They just pay for access and curate their purchases within its framework.

Yes, authors should be paid

Yes, authors should be paid.

But to shackle ebooks with the limitations of their physical cousins simply to create artificial scarcity seems like a great shame.

Surely any author would consider the exposure of their work to the maximum numbers of minds as or more importants as being compensated financially for it, no?

All I’m arguing is that we need to be imaginative in designing new systems for payment and distribution; the systems we’ve built to date are boring and limiting and show a distinct lack of imagination.

Hi Peter: You’ve “sparked”

Hi Peter: You’ve “sparked” some interest here.

I’m happy to say that a solution is on the way, at least for Canadian books. Have a look at www.deslibris.ca. And more specifically at http://www.deslibris.ca/en-us/…

As we say, this solution will not necessarily work for the larger publishers. But we think it will dramatically improve the degree of exposure and (hopefully, by extension) the revenue finding its way to Canadian publishers and their authors. It will also build stronger collections of Canadian works in Canadian libraries.

For example, look at the PEI Overdrive site to find books from Canadian publishers. Take Dundurn (one of the larger Canadian-owned publishers) as an example.

http://peipls.lib.overdrive.co…

Try doing an Advanced Search on this site for Dundurn. You’ll get a grand total of 3 titles which have been licensed by Overdrive to the PEI Library System. (And only 200 in the print catalogue.)

Dundurn has released over 1400 titles in ebook form. If (when?) the PEI system subscribes to desLibris, their readers will suddenly have access to all 1400 titles, which will all be available for Universal Loan.(Every book available to every reader all the time.)

Dundurn management, being a progressive group, are delighted with this new approach; they want people to read their books, and they know that a book that can’t be found can’t be read.

In agreeing to participate in the Universal Loan model, publishers need to make a small leap of faith, trading revenue today from the sale of a few books for continuing exposure of all books.

Libraries likewise need to make that leap, trading their traditional method (buy the book and put it on the shelf) for a new one (rent all the books.)

desLibris is being formally introduced to libraries and publishers at the library conferences coming up this month (including the APLA conference next week in Charlottetown.) We hope it too will spark some interest.

Add new comment