After seeing Laurie Brown’s live Pondercast in Wolfville in October, I became curious about whether she’d ever written a book, and this curiosity led me to her 1994 Success without College: Days and Nights in Rock & Roll TV. When a copy wasn’t available from my local library, I made an inter-library loan request, and it arrived to day, a copy from the Westmount Public Library in Quebec.

Both of my parents are retired professional classifiers-of-things: my mother a librarian, my father a geologist; it seems inevitable that some of this would rub off on me. Which is how I ended up taking a deep dive into the artefacts that the library applied to the book: the stamps, stickers, pockets and related classification numbers.

Let us begin.

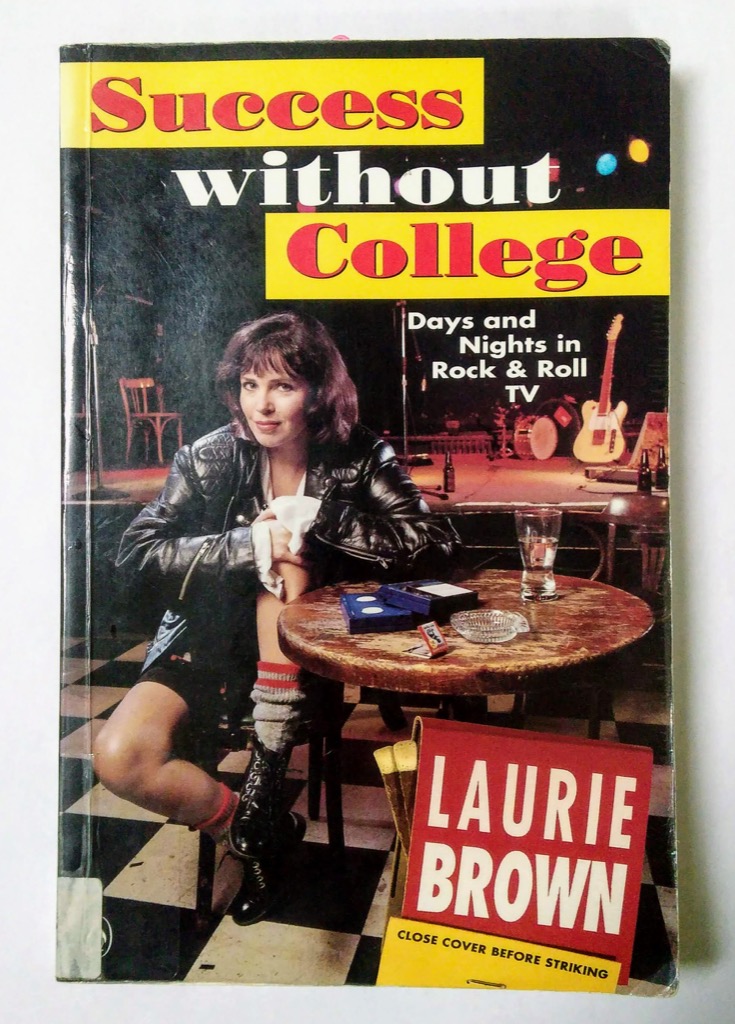

First, here are the front and back cover of the book:

|

|

While the front cover is free from ornamentation, the back cover has several ornaments, and we will start there.

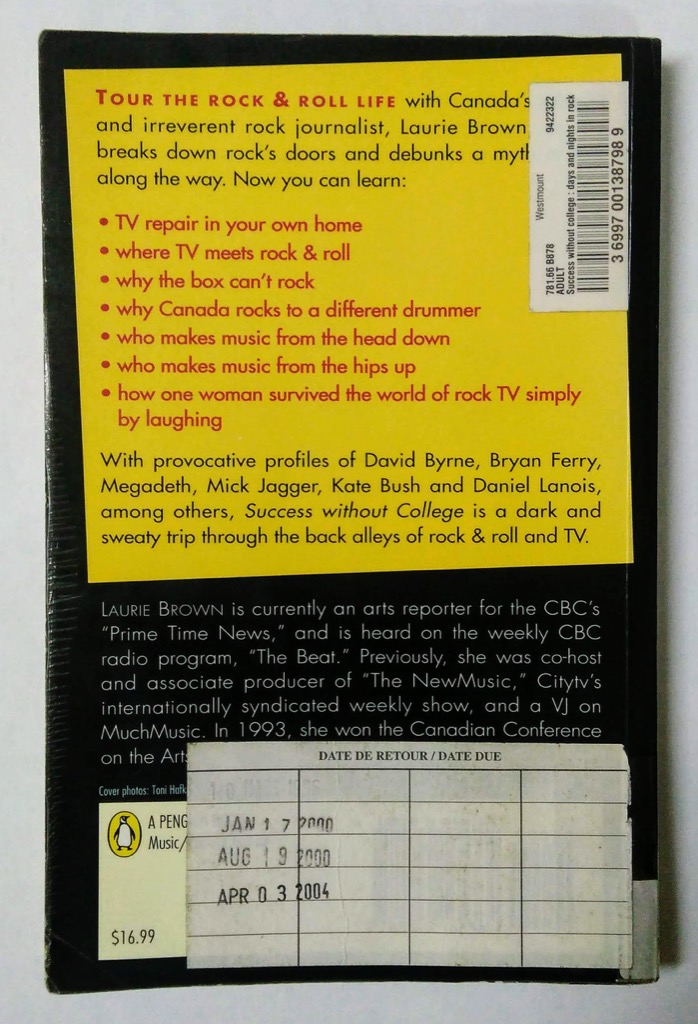

The Barcode Sticker

First, in the top-right corner is the barcode sticker. According to the Westmount Public Library’s history page, the library was automated in 1995, and I suspect this barcode came as part of that process.

There’s lots of interesting information on this sticker:

Dewey Decimal Number

This is the Dewey Decimal Classification System number for this book, which, as a non-fiction book, identifies its subject matter. The Dewey system, like the US ZIP code and Canadian Postal Code systems, moves, from left to right, to increased specificity:

700 - Arts & Recreation

780 - Music

781 - Genres & Theories

781.6 - Genres

781.66 - Rock

So the 781.66 tells us “this is a book about rock music.”

Other books in the Westmount Public Library’s collection with the same Dewey classification include Shake it up: great American writing on rock and pop from Elvis to Jay Z, The history of rock ‘n’ roll in ten songs, and We gotta get out of this place: the true, tough story of women in Rock. These books would appear on the same shelf in the Westmount Library as Laurie Brown’s book.

Cataloguing is as much art as science, so there’s no guarantee that any two libraries will use the same Dewey number for the same book; for example, the Toronto Public Library catalogues Success without College as Dewey 306.484, which is “Social Sciences > Social Sciences, Sociology, Anthropology > Culture and Institutions > Specific aspects of culture > Recreation and performing arts > Music, dance, theater.” Indeed it’s this Dewey number that appears printed as part of the “Canadian Cataloging in Public Data” inside the book, so Westmount decided to go its own way on this.

The order these Dewey 781.66-classified books would appear in on the shelf is determined by the second number, the B878, which is called the “Cutter-Sanborn Number,” used to assist in shelving books alphabetically by author’s name.

There’s an algorithm for converting the name of the author into an alphanumeric code; there’s a helpful website here that can be used to find the Cutter-Sanborn code for an author’s name, and, sure enough, the code for Brown, Laurie is B878. Before the advent of digital tools like this, a table of names and codes was used; here’s an excerpt from the book Explanation of the Cutter-Sanborn Author-marks (three-figure Tables), that served as a guide to using these tables:

Some persons are apprehensive that this decimal arrangement will be hard to use, or at least hard to teach to stupid assistants and (when the public are allowed to go to the shelves) to a public unwilling to take the trouble to comprehend. It may be so sometimes; I can only say that I have never had any difficulty with anyone, boy or girl, man or woman, when the arrangement was explained as it is above.

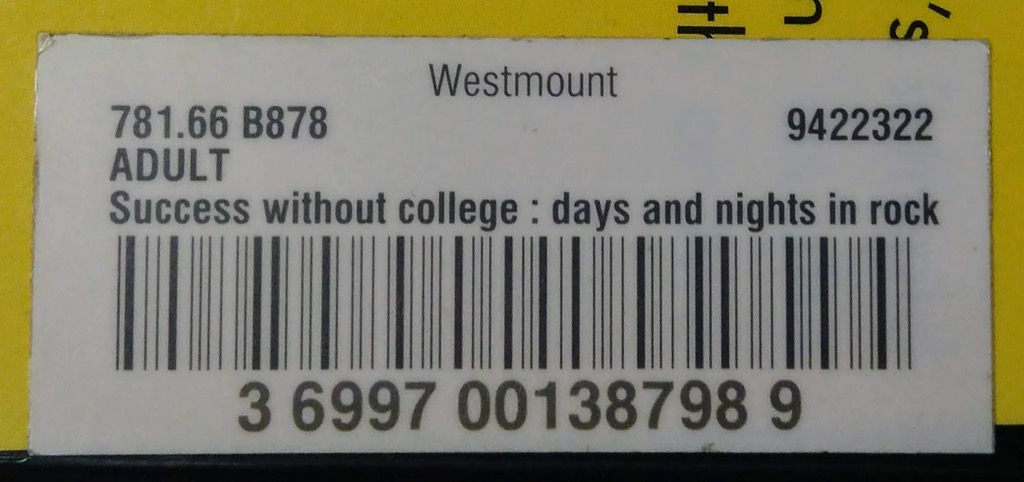

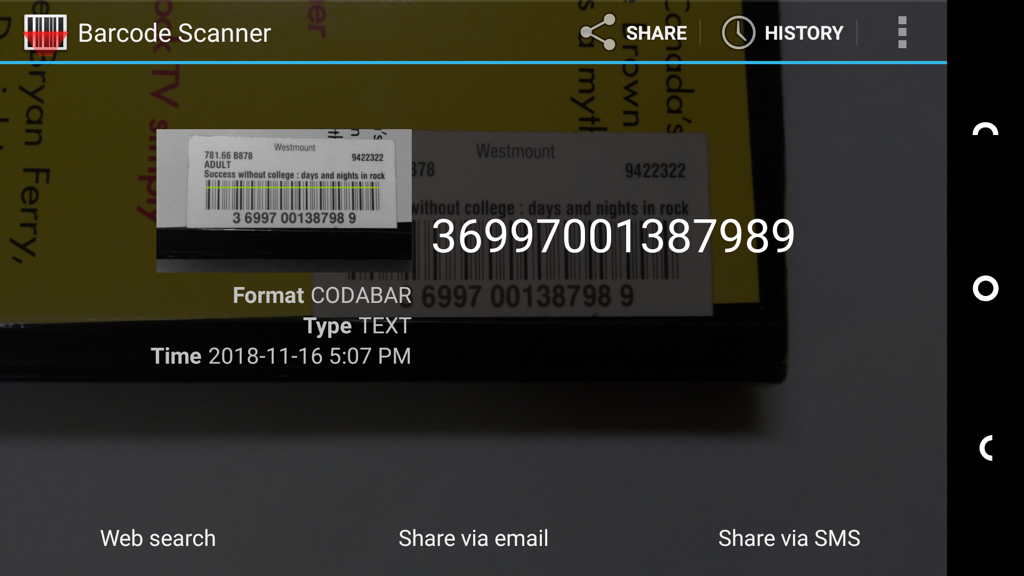

The Barcode

Under the Dewey number, and the title of the book, is the barcode itself, which looks like a UPC code that you see on products in a grocery store.

The barcode is nothing more than a scanner-readable encoding of the number that appears under it, 36997001387989, and that translation from encoding-to-number can be done by a barcode reader or, these days, by a barcode scanner app on a mobile phone.

Here, for example, is what I see when I scan the code with my Android phone:

Barcodes come in different flavours, and as you can see in the barcode reader screen shot, the flavour used by Westmount is CODABAR, a system developed in 1972 by Pitney-Bowes; it’s the same system used to encode, among many other things, FedEx airbills.

Accession Number

The number 9422322 appears in the top-right corner of the barcode sticker: this represents the book’s accession number.

The accession number is a unique ID for the particular copy of the book, and it’s generally assigned chronologically as new books arrive at a library. In this case the “94” represents the year the book was acquired (we’ll see this year show up below again, inside the book), and the 22322 is the unique number assigned to this copy (again, it appears inside too, in several places).

While all the copies of the same book in a library will share the same Dewey Classification Number, each copy will have a unique accession number to identify it; that’s why the number appears both on the book, and on all the stickers, labels and pockets attached to the book: it lets them all get matched up when and if they are separated.

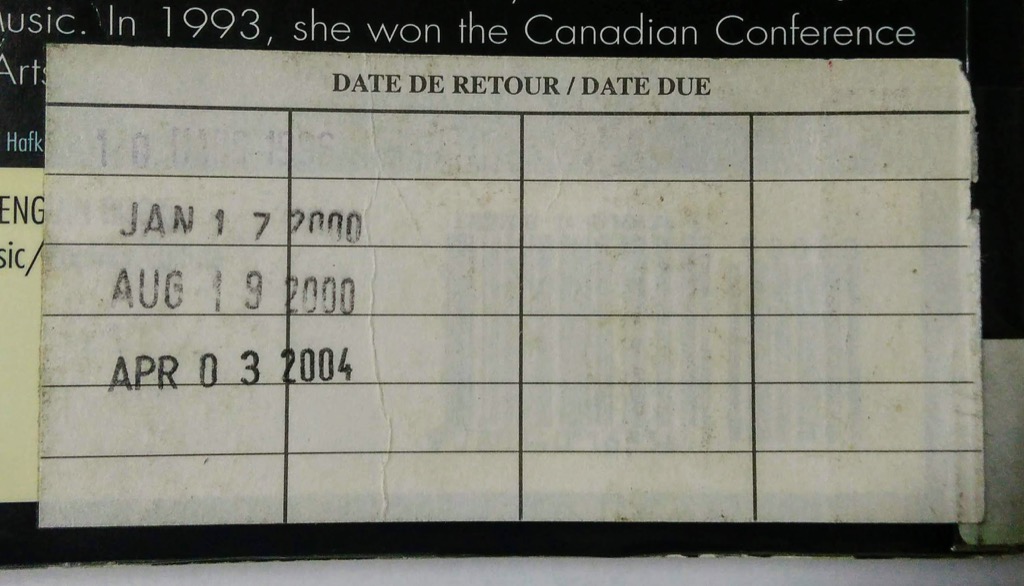

Date Due Sticker

Libraries have used a variety of systems over the years to tell patrons when the materials they’ve borrowed are due. This book is old enough to have spanned three systems, and this is one of them: a rubber stamp was applied to the sticker each time it was borrowed to indicate when it was due.

In this case there are four borrowing periods reflected, with due dates of March 10, 1996, January 17, 2000, August 19, 2000 and April 3, 2004. It’s likely that the 2 years between 1994 and 1996 used an earlier system, and the years since used some sort of receipt system that didn’t imprint the due date on the book itself.

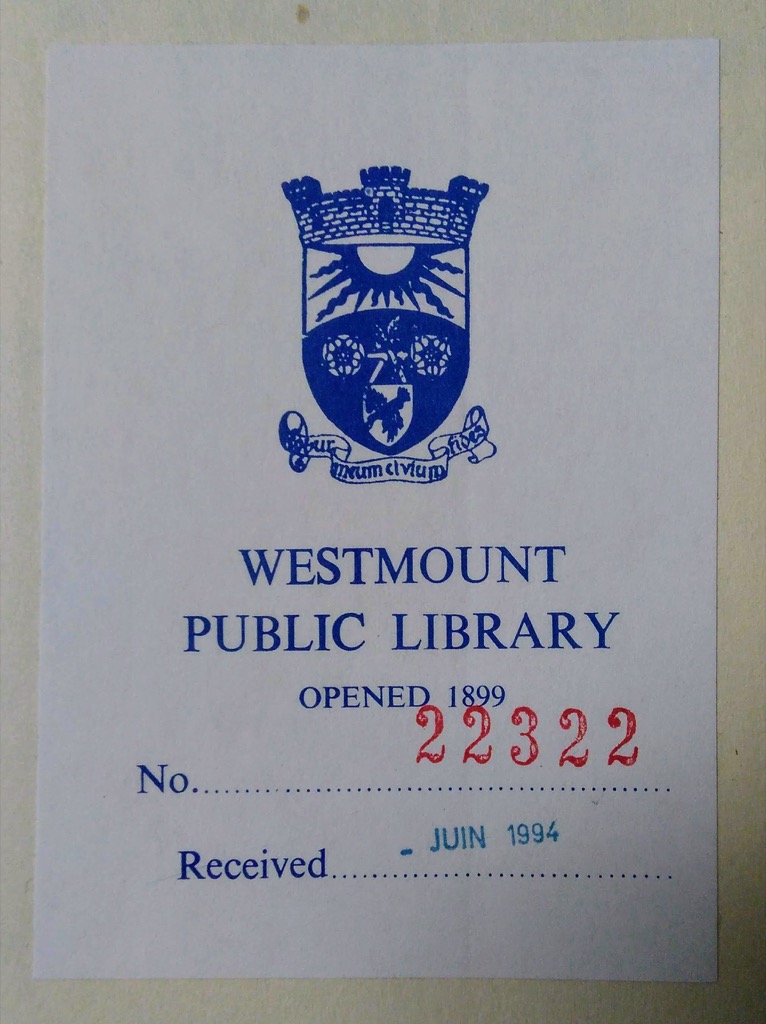

Bookplate

Moving inside the book now, on the first page there’s a Westmount Public Library bookplate, a piece of paper pasted onto the page:

City Crest

The bookplate begins with the crest of the City of Westmount, a coat of arms that’s described here in dense heraldic language:

Per fess enarched Or and Purpure, issuant from chief a demi-sun in his splendour Argent rayed Gules, in base a rose branch fesswise, slipped at each end and leaved proper bearing two roses Argent and pendant from the middle of the branch an escutcheon Argent charged with the raven of Saint Anthony volant and bringing bread all proper; Above the shield is placed a mural coronet of three towers proper.

The motto on the crest, barely visible on the bookplate, is the Latin Robur meum civium fides, in English My strength is the faithfulness of my citizens.

Opened 1899

Below the crest is “Opened 1899,” which undersells the historic position of the library as the first tax-supported public library in the province of Quebec.

The library building then and now, which is stunning, was constructed as project to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. From the book Polishing the Jewel, published in 1995, our man Cutter, he of the alphabetizing system, enters our story again:

Councillor J.H. Redfem visited libraries in the Boston area and the Westmount planners embraced the ideas he brought back. Most bore the typical features of architect Henry Hobson Richardson: an arched entrance topped by a gabled roof and peaked tower. One of five Richardson designs contained in a report by the Connecticut Public Library Committee of 1895 and 1896 was originally proposed for Westmount.

The final design would reflect the Richardson influence as well as Findlay’s neoclassical back- ground and the functional input of librarian Gould.

Interesting was a controversy surrounding the five Richardson designs. Librarians generally opposed his cozy reading rooms and alcoves, light chairs and small tables. Elizabeth Hanson, in Libraries and Culture (Spring 1988), says the dispute prompted renowned librarian Charles A. Cutter, of the Forbes Institute in Northampton, Mass., to declare: “I think from our experience of architects’ plans that we can safely say the architect is the natural enemy of the librarian.”

Accession Number and Date

Next on the bookplate is the first appearance on the inside of the 22322 accession number that we first saw on the barcode label and, below that, the June 1994 date the book was originally received.

Pencil Notation

At the top of the title page is a notation in the right corner: NH ¶ 991695:

This one had me stumped, so I sent an email to the Westmount Public Library, and a librarian there helpfully replied:

The number penciled in on the title page is an encoding of the following information: vendor, library, and cost. The vendor for this book was Nicholas Hoare. The library, Westmount Public Library, was encoded as 99. And the cost of the book at the time of purchase was $16.95.

Nicholas Hoare was a venerable Canadian bookseller with three branches, one each in Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal, the last of which closed in 2013. The Montreal store was on 2165 Madison Ave. in Montreal, a short 10 minute drive from the Westmount library.

Title Page

Accession Number

Turning the page, to the title page of the book, we first see another instance of the accession number, stamped at the top in lovely red numbers:

Dewey Classification Number

Under author Laurie Brown’s name on the title page, with “Brown” underlined in pencil, is the Dewey Classification Number again. I presume that “Brown” was underlined by the cataloguing librarian as a guide to what last name should be used in the calculation of the B878 Cutter number.

Library Address Rubber Stamp

At the bottom of the title page the name and address of the Westmount Public Library is rubber-stamped; the cheaper paper of the paperback book was not kind to the rubber stamping, and the address is smudged enough to be open to interpretation (it’s 4574 Sherbrooke St, Westmount, Que):

Back Page

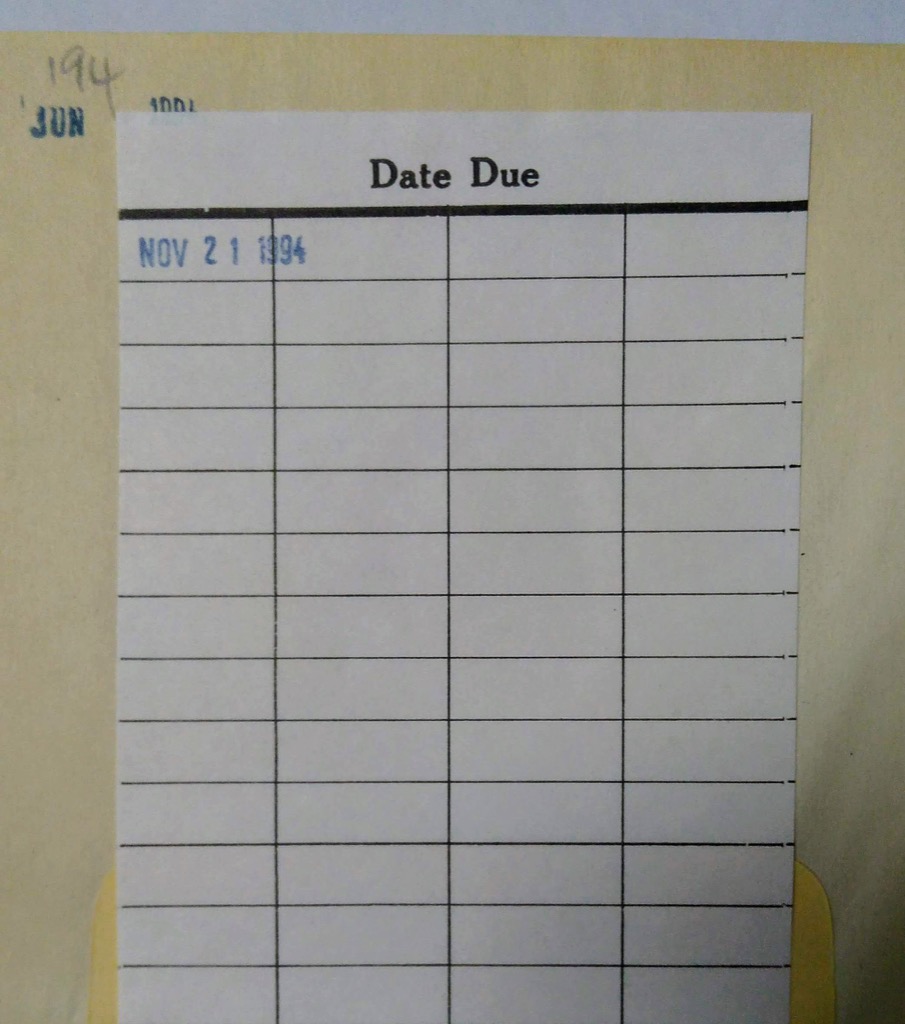

Date Due Slip

There are a variety of artefacts on the back page of the book, starting with what appears to be the first of the three generations of date due indicators, an index-card-sized grided sheet of paper, pasted at the top and titled “Date Due.”

There’s only one stamp on the slip, November 21, 1994, and I assume that’s the first time that the book was borrowed after its June 1994 acquisition (the June 1994 date appears under the slip of paper, rubber stamped); the date due sticker on the back picks up after this with a March 1996 loan.

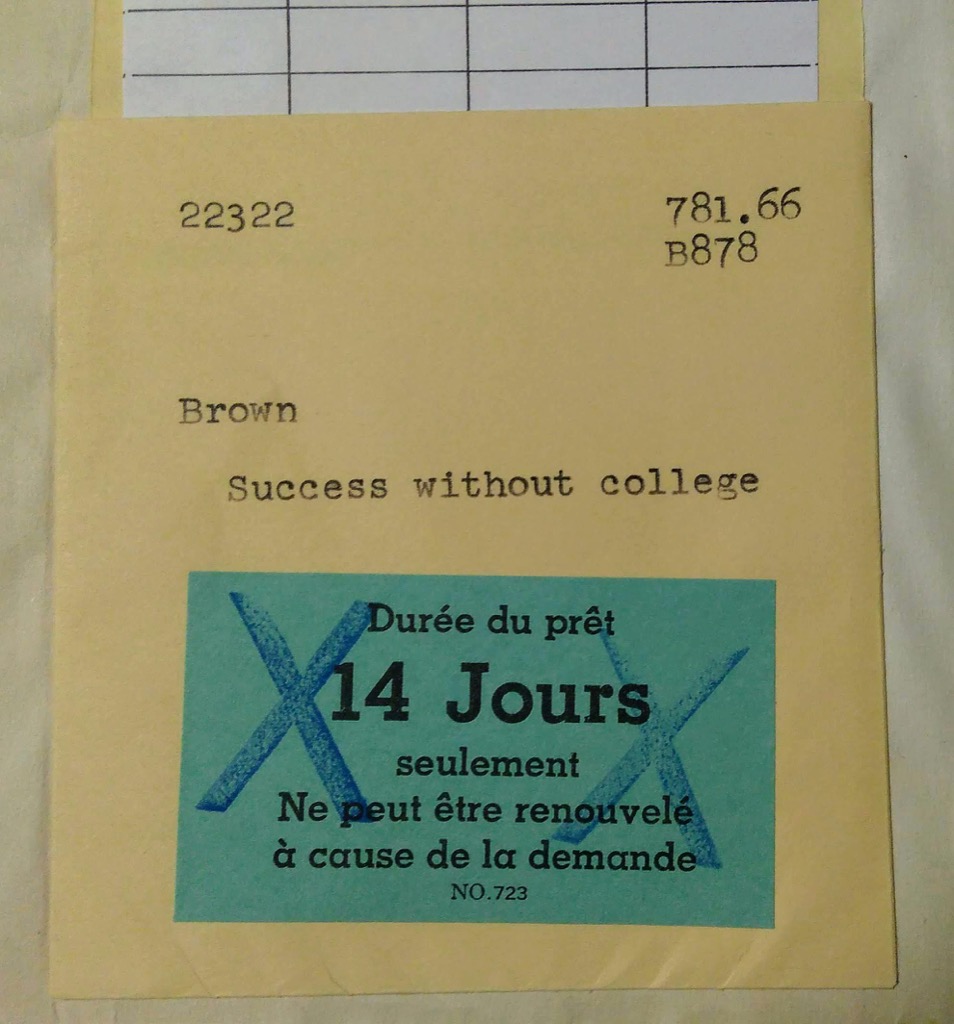

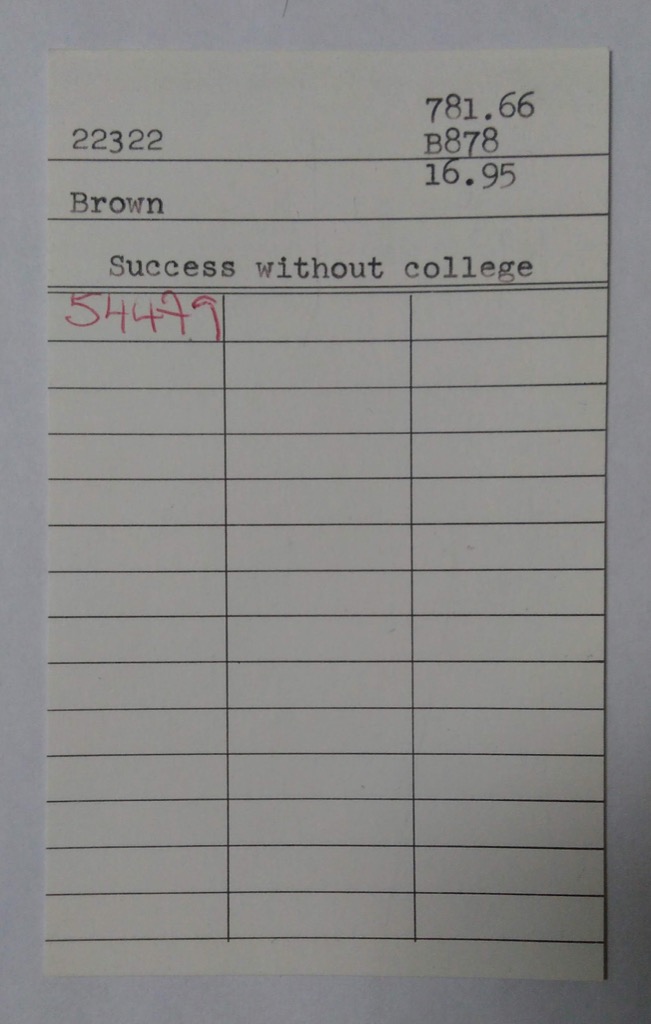

Card Pocket

Below this Date Due Slip there’s a card pocket with a card tucked inside it, with information typewritten on it:

At the top of the card pocket on the left is the 22322 accession number, and on the left is the Dewey number; below those appears the author Brown’s last name and the short form of the title of the book.

Below these is a blue sticker, in French, that reads:

Durée de prêt

14 Jours

seulement

Ne peut être renouvelé

à cause de la demande

In English this is “Loan duration: 14 Days only ¶ Can not be renewed due to demand.” The typical loan period, today, for a Westmount Public Library book is 21 days; it’s not clear whether the blue “X” marks over the sticker are for emphasis, or to strike out this restriction (I suspect the latter).

Card Inside Pocket

Inside the pocket is a card that contains much the same information as on the pocket:

The “16.95” below the Cutter number may be the price of the book ($16.99 appears printed on the back cover), or something else; the same digits appears in pencil on the title page in the top-right corner.

I’ve no idea what the handwritten-in-red 54479 represents; I assume that at one point, following the practice of other libraries, the card would have been used to record the due date for the book when it was borrowed, making it the third version of date due recording to appear on the book; it’s possible that the handwritten number was the ID of someone who borrowed the book.

Comparing the typewritten impressions on this card to those on the card pocket, it appears to have been typed at the same time on the same typewriter.

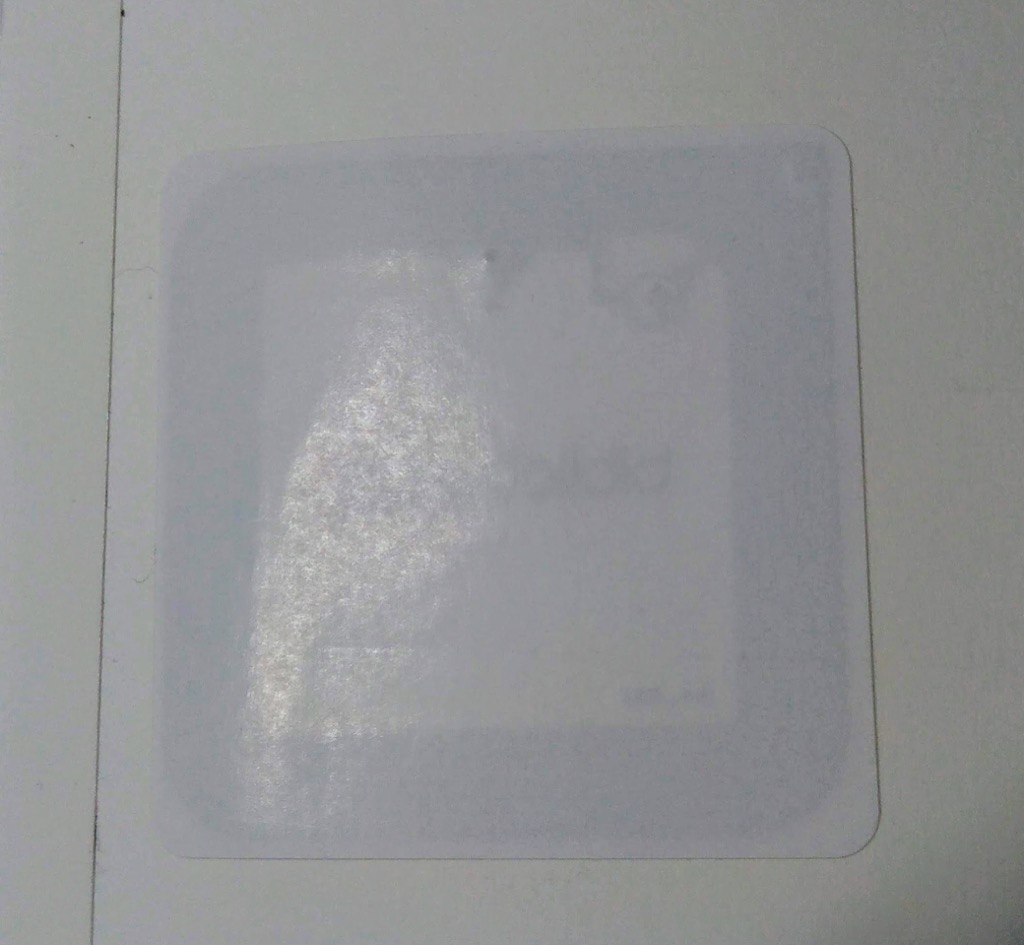

RFID Sticker

The final artefact on the book–and, I’m assuming, given the technology it represents, the most recently applied–is an RFID sticker on the inside back cover:

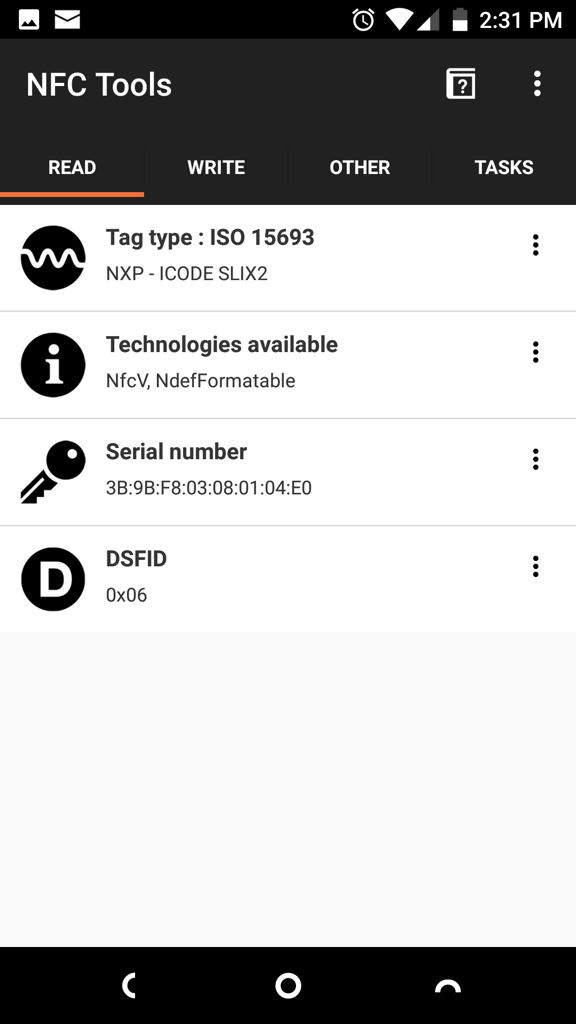

Because my Android phone is NFC-capable, and so can read RFID chips when placed near them, placing my phone against the book pops up the RFID serial number on the screen:

The chip embedded in the RFID sticker is of the type ICODE SLIX2, from the NXP company, a chip described the the maker as:

Contactless energy and data transfer

Whenever connected to a very simple and easy-to-produce type of antenna (as a result of the 13.56 MHz carrier frequency) made out of a few windings printed, winded, etched or punched coil, the ICODE SLIX2 IC can be operated without line of sight up to a distance of 1.5 m (gate width). No battery is needed. When the smart label is positioned in the field of an interrogator antenna, the high speed RF communication interface enables data to be transmitted up to 53 kbit/s.

The “easy to produce type antenna” is what you can see around the bounds of the sticker through the paper. The serial number that the chip communicates, the hex numbers 3B:9B:f8:03:08:01:04:E0, doesn’t appear to bear any relation to the accession number or the barcode number; if the library uses this as part of its circulation system, it’s possible that this serial number is keyed to the record in the library’s system somehow.

The RFID sticker may, instead or in addition to any role it has in circulation management, be used as part of the library’s security system or sorting systems: holding the cover up to a light I can see it’s made by Bibliotheca, which makes security systems, self-check systems, and sorting systems for libraries.

Success Without College

Laurie Brown’s book was published at a very interesting inflection point in the history of technology, both for its subject matter and the library accoutrements it carries.

Brown was a pioneering music journalist at the time when the heart of music journalism was television; from her introduction:

For many many years my career has been caught in that hard place, a place a bit dank, sweaty and infested, between the forces of rebellion (rock and roll) and the forces of capitalism (TV).

Almost a quarter century later, this dank place has moved on from television–do MTV and MuchMusic still even exist?–to the fragmented landscape of the Internet, and so there are now a million dank places, tucked away on YouTube channels, Facebook pages, Instagram posts and Spotify streams.

In the annals of history, that brief union of rock and roll and television may disappear into a forgotten blip; we’re lucky that Brown had the foresight to document it while still near the heyday.

The physical book and its library clothing, as I’ve tunneled into above, also tell a store of technological transformations of libraries; books today carry little of their circulation history on them, as this is squirreled away in digital systems, not stamped on the books themselves as we see here. And digital systems, constantly evolving and personalizing, contain none of this richness, as their history is measured in seconds, not decades.

That’s a shame, for a book that wears its history is a more interesting book. As Westmount automated in 1995, so did many public libraries, and as collections have evolved, there are fewer and fewer books like this one still on the shelves. I pity the literary culture anthropologists of the future.

Thanks to my mother (the librarian) both for the inspiration to be weird enough to find all this interesting, and for technical help putting this all together.

I am

I am

Comments

I am also weird enough to

I am also weird enough to find this interesting. Thanks for sharing! Signage rocks.

Final mystery solved: I

Final mystery solved: I updated the post to include this, in regards to the pencil marking:

This one had me stumped, so I sent an email to the Westmount Public Library, and a librarian there helpfully replied:

Nicholas Hoare was a venerable Canadian bookseller with three branches, one each in Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal, the last of which closed in 2013. The Montreal store was on 2165 Madison Ave. in Montreal, a short 10 minute drive from the Westmount library.

Dear Peter,

Dear Peter,

I found my way here after searching for more information about Westmount's civic motto.

I can say from many visits and purchases there that the actual Nicolas Hoare store's location was on Greene avenue, one of the main commercial streets in Westmount, just below (or south of) its corner with Sherbrooke street.

I am wondering now whether the address you cited, 2165 Madison avenue, may have been the storage facility or offices for Nicolas-Hoare-the-business.

I was very sad to see the shop on Greene close--it had a beautiful wood-panelled interior, with a mezzanine-style arrangement at the entrance between ground, basement and first floor, as well as a well-curated music section on the upper floor. The booksellers were welcoming and knowledgeable, and always so attentive towards shoppers, browsers and visitors: it felt like the spirit and essence of Montreal’s Anglo commercial heritage of long ago, distilled into one warm and traditional space... One half-expected there to be a Victorian tearoom at the back of the store--something along the lines of Bewley’s in Dublin or a Montreal-scale version of Fortum’s in London--but really it was just a great place to browse for and find new books, and run into a friend or neighbour, or have a conversation in English. Nicolas Hoare and the Bistro on the Avenue were two great losses from Greene, along with various small galleries and shops over the years.

Today I can’t help but feel that Westmount really lacks a good bookstore. Still, there is a community book sale, organised by the Westmount Library, which takes place at least once a year at Westmount’s Victoria Hall: it is a sight to see, as the space is large, and has always been filled each time I have gone.

Best regards,

Martin

Apologies for misspelling the

Apologies for misspelling the name--I meant to write Nicholas, not Nicolas, Hoare! Nicolas would be the French spelling of the name, so a Freudian typo on my part...I suppose those us left here really are bilingual, after all :)

M

Add new comment