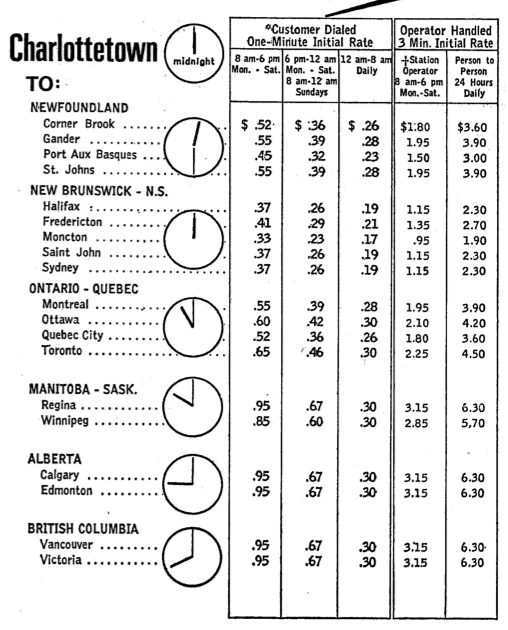

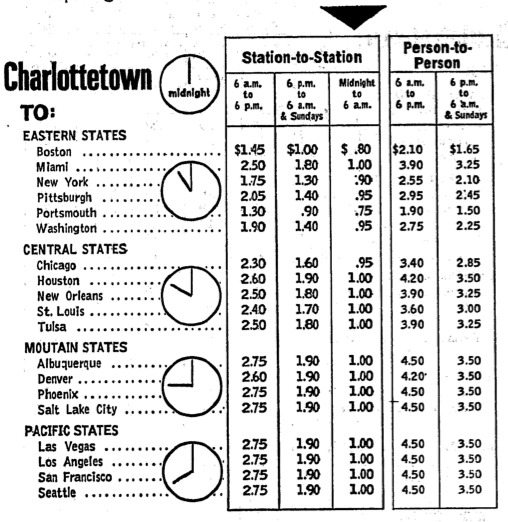

Here are the tables from the 1975 Island Tel directory listing the cost of making “station-to-station” and “person-to-person” long distance calls to Canada and the United States. Wikipedia summarizes the two call types nicely:

- A person-to-person call is an operator-assisted call in which the calling party wants to speak to a specific party and not simply to anyone who answers. The caller is not charged for the call unless the requested party can be reached. This method was popular when telephone calls were relatively expensive.

- Station-to-station is a method of placing a telephone call, with or without assistance, in which the calling party agrees to talk to whoever answers the telephone.

On the Canadian chart the rates are per minute, with a one-minute minimum; the most expensive station-to-station call you could make was during the day from Monday to Saturday from Charlottetown to Manitoba or west for 95 cents a minute. This call would cost you $57 if you talked for an hour.

On the USA chart the charges are for a minimum 3-minute call, so you divide by three to get the per-minute rate. The most expensive call you could make within Canada and the United States in 1975 was to the west coast of the USA which, during the “prime time” of 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. would cost you 91 cents a minute, or $54.60 an hour.

Right now, 38 years later, the most expensive “station-to-station” call I can make is the $9.29 a minute ($557 an hour) it would cost me to call an Immarsat Atlantic phone.

But that’s an exception to what, otherwise, are frightfully low rates by comparison.

For the same 91 cents a minute I could call Seattle for in 1975, I can now call a mobile phone in Romania or a land-line in rural Chile.

For 80 cents a minute I can call Easter Island, Kiribati, or a mobile in Greenland.

For 50 cents a minute I can call a mobile in the Morrocan desert or land line in Senegal or Djbouti.

For 10 cents a minute I can call mobiles in the Czech Republic, Australia and Brazil and land lines in Bolivia.

And for a penny a minute – 1 cent! – I can call land lines in Korea, Turkey, Mexico, Brazil, and Taiwan and mobiles in India.

Calling someone at a penny a minute means that staying on the line for 24 hours would cost you about $14. Which is the same amount you could have spent in 1975 on a 15 minute call to Vancouver.

What I find facsinating about all of this is that for people of my generation and older this dramatic decrease in the cost of long distance has never really hit home: we still have, buried deep our our subconcious, the impulse to “wait until after 6” to call (for better rates) and the sense that calling anywhere beyond Summerside is something that you have to be careful about because you could go broke.

For me to pick up the phone in my office right now – in the middle of the day! – and call my friend Olle on his mobile in Sweden would cost me 5.5 cents a minute. And yet I would never, ever think of doing that. Even trans-Atlantic Skype, with no per-minute fee, seems exotic and like it must be rationed.

“Economic sense memory” is long-lasting and hard to shake: it’s why my grandmother would walk up the hill to Callbeck’s in Brantford to save 5 cents on yogurt when it was on sale; she came of age in the depression and saving 5 cents was something she would never pass up the chance to do, no matter how far she had to walk or how much time it took out of our day.

I’m pretty sure that Oliver has no notion at all of what “long distance rates” are: he’s been video chatting with his grandparents his entire life, and thinks of instant global communication as he thinks about shouting across the street. He’s shaken the curse. And that’s probably a good thing.

I am

I am

Comments

When my family came from

When my family came from Russia to Toronto, long distance calls were also a strictly after hours weekly affair, especially on an immigrant’s limited income. Over the years, I noticed different milestones along the way. First came the calling cards with bizarre name like Sifa and CiCi (which are still sold in Toronto convenience stores). It meant calling at any time, but you were still limited to long conversations, as you’d be docked with connection fees.

A couple of years later, calling cards without connection fees came along and a leisurely call was finally practical. It was always slightly less convenient than direct dialing, but you knew as an immigrant, you couldn’t have all the luxuries.

Eventually rates came down, and a calling card became just another thing you’d buy at the same frequency as milk or eggs, with the same frustration when you unexpectedly had an empty card.

Now in 2013, I signed up for a Skype to Go deal with unlimited minutes and a number that’s just programmed into the address book.

Holy smokes, it’s the future!

Add new comment