The German Netflix series Dark, which I’ve now watched through, and loved all three seasons of, returns to a parable several times:

A human lives three lives. The first ends with the loss of naiveté, the second with the loss of innocence, and the third with the loss of life itself. It is inevitable that we will go through all three stages.

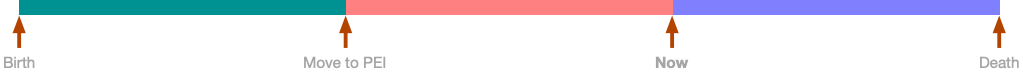

I have now spent more of my life on Prince Edward Island than off, a milestone I reached mid-March when the clock ticked over 27 years. Because Catherine and I moved here only 18 months after meeting, “life on Prince Edward Island” overlaps to a great degree with “life with Catherine”: PEI is the stage upon which our lives together played out.

So my life now neatly divides into three (I’m choosing to be optimistic about having another 27 years in me):

It doesn’t take much to shoehorn this into the Dark construction, as moving to PEI did coincide with a certain loss of naiveté, and the death of my father and of Catherine involved a rather dramatic loss of innocence.

June and July were therapeutic months for me: I did a round of one-on-one therapy with my psychologist, and, in parallel, attended an 8 week men’s grief group (which I dubbed “grief club” to my fellow bereaved).

The life lesson from both, boiled down to their essence, is “feel all the feelings.” Easier said than done, especially when you try to do it all by yourself, which is how I’d been attacking the problem from January to June. Indeed, when the instigator of grief club phoned me one Friday in late spring to invite me to join, my first reaction was “thanks, but I’m okay.”

On Monday I changed my mind, phoned back, and signed up. I booked my first appointment with my psychologist on the same day.

Truth be told, the most important part of both experiences happened that day: the simple act of saying, to myself, “no, I don’t got this” was the most important step of all.

Catherine died 200 days ago; I’ve spent much of that time dwelling on the years we spent together, on her illness and death, and trying to figure out the practicalities of how to live now, as a single father and a single man.

I’ve also spent a lot of that time running away from feeling (I uttered the phrase “I’m not sure if it’s okay to feel this” more than once during therapy), and trying desperately to attach some sort of blueprint to what happens next.

That lack of a blueprint is daunting: I’m so, so used to having a blueprint, most recently the sad and inevitable blueprint of Catherine’s illness and death, that not having one left me grasping every which way for one. It was my brother Mike who pulled me out of its whirligig, telling me, when I proclaimed frustration at not knowing what the coming months and years would hold, that it’s okay to not know, that, for that matter, it’s not possible to know. That was good to be reminded of.

So “now until death” lays out before me. The purple era. Twenty-seven years of?

I vacillate between seeing it as a free and open road and a frightening forest path, but I’m spending more time in the former these days. There is a power in the loss of naiveté and innocence, something I didn’t anticipate: I have been to the top of the mountain; it is dreadful and sad and terrifying, but it’s also beautiful and full of promise to look out from that vantage point, and empowering to have made that climb and survive.

A friend of mine, consoling me after the death of my father, said that he had never felt so intensely alive after the death of his; I know exactly what he was talking about.

What’s next?

I am

I am

Comments

I really appreciate that you

I really appreciate that you share these difficult and painful questions and your honest search for answers. Sometimes there are no answers, no map or plan to guide us and we have to accept that and just breath in the moment. Thinking of you and wishing you well.

Add new comment