It seems as though every decade or so I’m destined to revisit a talk I gave — “Adventures on the Information Red Clay Road: Getting Wired Cheap” — at Access 1994, a conference of technically-minded librarians held that year in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Ten years ago Art Rhyno at the University of Windsor found the text from his personal archives — my copy had long since vanished — and he kindly passed it along. I found it again today when looking through my archives, and, as any good archivist would do, took the time to bring it forward a generation or two of content management systems so that it can live on for another decade.

I wrote the talk using the Unix ‘vi’ text editor on a DEC VAX computer in the library a Memorial University the day before I was scheduled to deliver it. What strikes me, 18 years later, is that I still strongly believe in the message I was delivering then; if anything I believe in it more strongly.

What I hadn’t noticed in previous looks-back at this text is that buried within it is the date that the first website on Prince Edward Island went live: July 11, 1994. It’s not there any longer — www.crafts-council.pe.ca went dark a few years later — but without my experience developing that first website I wouldn’t have gone on to work on the www.gov.pe.ca project for 8 years, and my life would have taken a very different tack.

So, here’s the text of my talk, as I delivered it.

Adventures on the Information Red Clay Road: Getting Wired Cheap

Good afternoon.

I’d like to talk about three things today, three things which roughly correspond to the title of this talk:

First, I’m going to talk something about Prince Edward Island and about our red clay roads.

Second, I’d like to tell you a bit about what my organization, the PEI Crafts Council, has been doing using client/server tools.

And, finally, I’ll explain what I mean when I talk about this “information” red clay road and why I think it’s important.

I’d like to start, though, with a poem…

Home names

Are fond

And they are chantable

To the heart far-wandered,

Island-born

And therefore

Not transplantable.Red clay soil

Is strongly lovable,

Dear-folk-dust

Thickened to the soul;

Home lanes are friendly,

Walkable,

Along the ways

Neighbours

Time-enough-to-talk-and chat-able

InclinedO, I find home names

Fond,

And home things chantable

Cosy to the mind.Flying home

Is dear,

Warm,

Excitable:

Through

The gray-wool clouds

Dropping down,

Slow-curve slicing

To the ground:

From the mainland hopping,

When I’m

M.C.A.

Round-trip

Six-day stopping,

Gayheart,

Early-Birding

Home.

That was written by a Prince Edward Island poet, A.P. Campbell, and published in a book called “Red Clay Soil.”

What you see on the screen in front of you is a red clay road on Prince Edward Island. Prince Edward Island, for those of you who don’t know, is Canada’s smallest province, an Island located between Newfoundland and the mainland, about 10 kilometers off shore. There are about 130,000 people who live on the Island year ‘round and we are joined, over the course of each summer, by an additional million-odd tourists. The Island’s economy is based on farming, fishing and tourism and, like the rest of Atlantic Canada, we haven’t been particularly well off for the last hundred years or so.

PEI is known as the “Birthplace of Canada” because, in 1864, a conference was held in what is now our provincial legislature, Province House, which, although not originally intended as being so, turned out to be the occasion for the signing of a somewhat formal agreement to proceed with plans for what became Canada. What is not very well known is that Prince Edward Island itself was not a signatory to this agreement, deciding to remain a colony of Great Britain instead. At the time, there weren’t many compelling arguments for PEI to join, it being a relatively well-off place, a centre for ship-building that traded as much with they called “The Boston States” as with what was then “Upper Canada.”

It was not, in fact, until 6 years after confederation that PEI got around to joining Canada, and this only because an over-zealous programme of railroad development had lead to an over-leveraged treasury, something which Canada agreed to assume if PEI joined up.

PEI is essentially made of red clay. It is everywhere. And so, when you build road on the Island, what you end up with, after scraping away all of the trees and the plants and the topsoil, is red clay roads.

Like the one here.

At one time in the not too distant past, all of the roads were red clay roads. They are, alas, a disappearing species, gradually being paved over by governments eager to please their constituents.

This is not surprising as for two months each spring, red clay roads go from being the idyllic paths that you see here to being long red stretches of extremely deep, extremely unforgiving, red muck. If you can pave someone’s road and save them the long walk in from the main road every spring, you have, politicians reason, a good chance of winning their hearts and their vote.

There is an interesting story concerning this, in fact. The election of 1966 was a particularly hotly contest one. Island politics is unlike politics anywhere else in ways which it would take much longer than we have here to explain; suffice to say that, for as long as anyone can remember, there have been roughly 50% of people who are die-hard Liberals, and 50% who are die-hard Conservatives. The 1966 election was remarkable, in part, for the fact that one of the Liberal candidates, in the riding of First Kings, died suddenly after the date for nominations had passed but before the election. Under PEI’s elections rules, the death of any candidate required that the date for the election in that riding be set ahead to allow for campaign of the proper length to be waged. So whereas the rest of PEI went to the polls on May 30, 1966, the residents of First Kings had to wait until July 11.

This in and of itself is not particularly remarkable. What is remarkable is that the results of polling on the night of May 30 was after all the recounts had been completed, a dead tie: 15 Liberals, 15 Conservatives. The entire fate of the Island’s government, thus, lay on the shoulders of the voters in First Kings.

As you can imagine, the ensuing six weeks, as one book puts in “resembled a theatrical farce.” The first thing the incumbent Conservative government did was to have its Minister of Public Works resign, to be replaced — by sheer coincidence they claimed — by the candidate for First Kings. It is estimated that in that short six weeks, a grand total of 30 miles of First Kings roads made that transition from red clay to shiny new paved roads. One farmer is rumored to have erected a prominent sign reading “PLEASE DON’T PAVE: THIS IS MY ONLY PASTURE.” Other Islanders are said to have jokingly wondered how it was that the eastern tip of the Island didn’t sink into the sea under the weight of all of the road machinery.

Ironically, when all of the ballots were counted on July 11, both seats went Liberal, the government of the day was defeated, and First Kings went back to just being another one of the Island’s 16 ridings. Albeit a very well paved one.

I tell this story not only because it’s a particularly interesting one, but also because it illustrates how public policy, especially public policy that relates to such charged issues as transportation and communications, gets shaped.

Despite all that I have just said, the fact remains that red clay roads are stunningly beautiful pieces of road to drive along. They are not efficient, they are not the fastest distance between two points, and even in the midst of a hot dry summer they can present an interesting driving challenge. But when you are driving down a red clay road, you know that you’re on Prince Edward Island, you feel that you’re on Prince Edward Island, and that feeling is a difficult feeling to describe. If I had the choice of living on a red clay road or on one the sleek new modern roads, I would take red clay, challenging spring muck course and all, in a minute.

I’ll finish this section of my talk with this message:

“The revolution that has taken place in the state of communication in Canada, and with that change the enormous advance in all matters connected with civilization, within the last twenty years, is perhaps as astounding as the world ever saw.”

That is a passage from a lecture given by a man named Alexander Murray to a St. John’s audience on March 26, 1877. He goes on to say…

“But in Canada, as well as in Scotland, the less intelligent classes were hard to move out of the old groove; and well do I remember, after good plank or macadamized roads were constructed, how these people clung like like parasites to the old tracks; carrying half-loads, wearing and tearing both wagons and horses ruinously, rather than pay a sixpenny toll for easy, rapid and safe communication.”

I quite proudly, in other words, count myself among the wretched parasites.

You may rightly be asking at this point in the talk: “well, that’s all very well and good, but what the hell does it have to do with Client/Server Computing: Information Access in the 1990s.” Before I answer that question directly, I’d like to something about how my organization, the PEI Crafts Council, has been involved in “information highway — or, as I prefer — “information red clay road” endeavours.

The PEI Crafts Council does pretty well what you expect something called the PEI Crafts Council would do. We are the provincial organization on Prince Edward Island servicing and representing crafts producers… we operate a retail crafts store in Charlottetown, hold crafts exhibitions and fairs, represent the crafts industry to government, and provide training, education, and information resources to crafts producers.

One of our information projects, the one with which I am involved, is called the “Crafts Information Service.” It is simply designed to help crafts producers in their search for raw materials, tools, equipment and services. On Prince Edward Island, as in Newfoundland and many other remote areas, finding information about “where to get what” if you’re a craftsperson is often a daunting job, something which, even if you do succeed, takes lots of schlepping around libraries and lots of expensive phone calls. My task is to canvas North America — and in some cases the world — for the “where to get what” information and to organize and index it all with the help of a computer so that I can answer requests from craftspeople like “where can I find sources for brown mohair yarn” or “is there a source for bubinga in New Brunswick?” or “give me a list of Cross Stitch suppliers in Canada.”

And, for the last year and half, that’s what I’ve been doing.

Now this is never a project that was envisioned as using things like the Internet to deliver information. The number of craftspeople on PEI with computers and modems can be counted on one hand, and besides, it’s an awfully small place anyway, so it’s not usually a big deal for someone to drop in to our office when they’re in town for the day to look up information with our help. In most cases we’re not responding to crafts supplier emergencies, we’re helping curious craftspeople who want to expand their product line or find a new source for something or try out a new technique with new materials. Time is usually not of the essence, and doing things by visit, mail and phone is just fine for reaching an Island audience.

But then we realized that we were going to have to pay for this now-valuable information resource to be maintained and updated over the long term. Or, more properly, we stopped ignoring what we had known all along. And so we needed a way of having the service pay for itself.

At the same time, other crafts organizations in North America began to get word of what we were doing, and began to express an interest in having access to our information for their own members.

The solution we pursued to, at least in theory, address both of these needs, was to strap our computer onto the Internet and give people and organizations from away direct access to our information. The collected bits of money from a much wider audience, we reasoned, would pay for the upkeep of the database and, as a pleasant side effect all of our hard work would be helping a much broader range of craftspeople.

Actually doing this has not proved all that difficult.

We applied to CANARIE’s “TDTD” programme for funding, got turned down, reworked the application and resubmitted it under their “Operational Network Products and Services” programme and were successful. Although I am over-simplifying a lot of text juggling and number crunching and quick dashes to catch the Purolator guy, it seemed relatively easy, when all was said and done, to convince CANARIE that we had a good idea and could pull it all off.

And so off we went. The money we got from CANARIE added to some of our own, left us with about $22,000 to get the project off the ground and to keep it running for the first year. Of that $22,000, five thousand dollars is going to PEINet and the telephone company to strap us to the Internet, $15,000 is going to my salary, $1500 is going to overhead. If you do the math, you’ll realize that that left us with a total of $500 to cover software and hardware costs. Not, in the world of information service providers, big bucks, but I tended to take that as more of a challenge than anything else.

Now because the nuts and bolts of all of this are usually hidden away in air conditioned vaults deep within computer centres, I thought it might be illustrative to show you what it actually is I mean when I say “getting strapped to the Internet.”

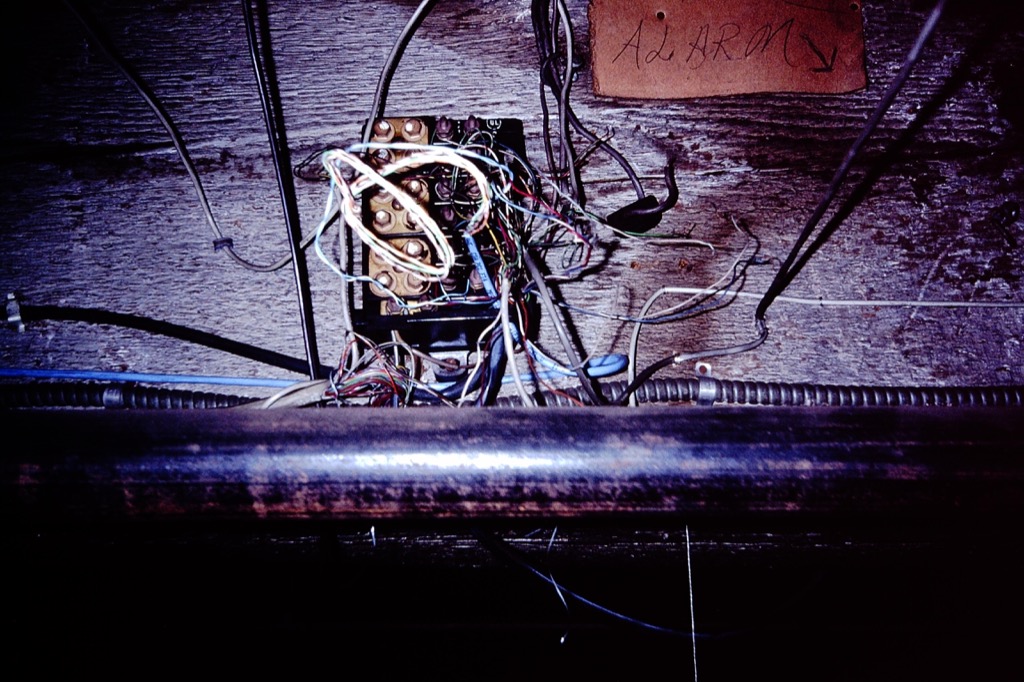

That little grey box over in the corner is just a regular old phone jack like the one it your kitchen. The phone company uses sleek grey ones for data lines for some reason. The grey wire running into the grey box runs out of a standard modem that we bought up the road for $300 or so.

From that grey box, a wire runs through what turned out to be a floor about 8 inches thick, down into our basement…

Where it then runs around through the boiler room to an old phone company terminal block…

And then up and through an old window, up the side of the back of our building…

Along to a phone pole on the street…

Along Sydney Street to Queen and up Queen Street…

To the IslandTel building at Queen and Fitzroy where it goes into the PEINet complex — which I wasn’t allowed to take pictures of for some strange reason…

…and then up to the roof with all of the other PEINet traffic destined for the mainland on the microwave link with Nova Scotia.

And that’s our little piece of the information red clay road.

But I digress.

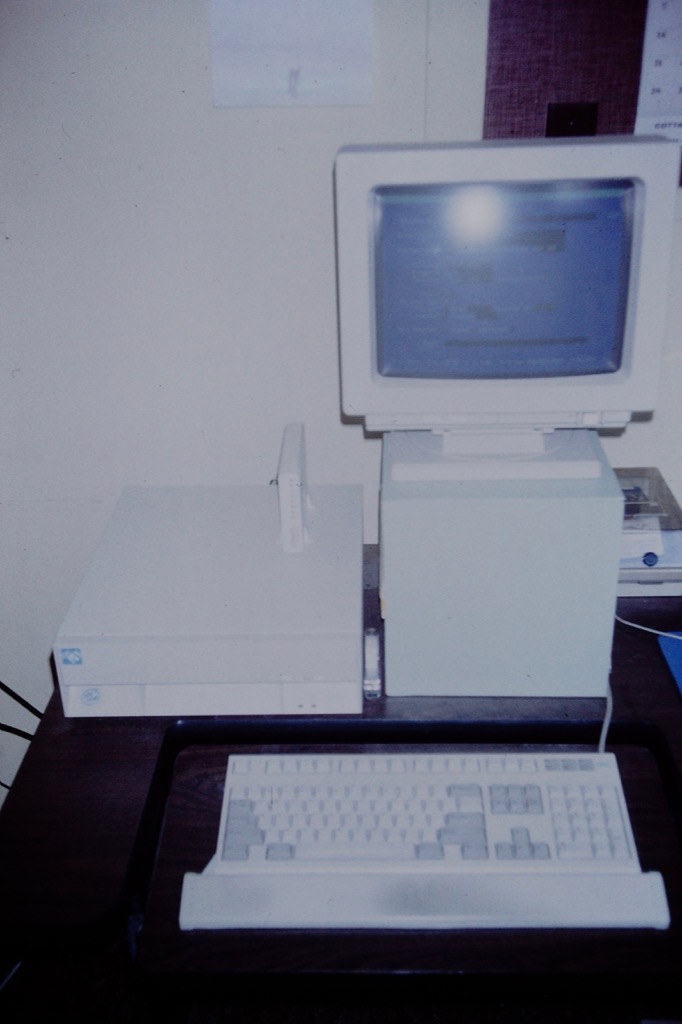

I took the same $1500 IBM PC that we’d been using to store our database and converted it from being a plain old MS-DOS machine into being a UNIX machine using a free version of UNIX called Linux that we got from an ftp server at the University of North Carolina.

I took our $300 modem and established, under UNIX, a fulltime connection with PEINet, and the Internet beyond, using SLIP.

I grabbed the Gopher and World Wide Web server programs from that same ftp site at the University of North Carolina and got them up and running.

And then I took our old MS-DOS database files, massaged them a bit, wrote some programs under UNIX to allow them to be searched, and plugged our Gopher and World Wide Web servers in.

I put notices up in the various crafts related newsgroups and got us listed in the InterNIC and Gopher jewels directories, wrote a short FAQ file about how to get to us, and opened the door.

Since we went “live” on July 11, we’ve averaged about 300 Gopher hits a day, with about half as many Web hits. Roughly 1500 people have searched our database which, if your extrapolate out over a year at the same level of usage, would mean 9000 searches a year and a cost to us of just over $2 a search.

The level of interest that has been shown has, I think, confirmed our suspicion that we have a valuable body of information, albeit one which is valuable to a very select group of people.

Has the money started to roll in?

No. The way we “charge” for information is to send out a “this is how much it cost us, roughly, to give you this” explanation with each list of suppliers that goes out the door or over the wire. We invite the peron who received the information to send us a donation of that, or any other, amount to help keep us alive. About one in four people who drop in or give us a call or send us a letter end up, once we send them something back, sending us back some money. So far, after almost two months and 1500 searches, I’ve received a grand total of $10 from Internet users, all in one cheque from a kind woman at Carnagie-Mellon University in Pittsburg.

Clearly, at least so far, the Internet experiment hasn’t lived up to its economic promise.

This is not exactly unexpected, although I must confess to finding it somewhat surprising. The Internet has traditionally been a place for “free” information, largely due to the good graces of universities and governments. The idea of charging for, or even asking for donations for, information on the Internet isn’t exactly part of the corporate culture of the place.

But we haven’t given up hope. We’re experimenting with digital cash as a donation option, and will probably soon be able to accept VISA and Mastercard donations using encryption features in the next generation of servers. While we would prefer to remain a “pay what you can” system, we might move to a “pay this, then add what you can” system if the cash doesn’t start rolling in soon. We don’t have a lot of time to experiment, but we do have a little, and we’re going to take advantage of it.

Now I have purposefully made all of this seem somewhat simpler a process than it has actually been. But not by too much. While I am not exactly a computer neophyte, I’m not a dyed-in-the-wool hacker by any means. This conference was the first time I’d actually heard anyone say WWW out loud. I’d really never used UNIX before last year and had no idea how to set up a Gopher or a Web server before about three months ago. And I am not a magician.

I say all of this to because I’m particularly concerned that you realize that although what we have done at the Council is novel, largely because of the size, nature, and location of our organization, it is by no means revolutionary, innovative or even all that interesting in absolute terms.

Our little experiment might prove to be useful and valuable and we might move to offer additional information in this way. Or we might decide the whole thing was a silly idea and chalk one up for experience.

And now I’d like to go back and talk some more about red clay roads.

Red clay roads are stunningly beautiful. The may turn into seething muck ponds for two months out of every year, they might not be the shortest distance ebtween two points, you can’t really force your car to hurry along a red clay road. But they are beautiful. When you drive down a red clay road, you know that you are in Prince Edward Island, you feel as though you’re in Prince Edward Island, and that is a feeling that cannot be adequately described in words.

Highways are ugly. They might be fast and efficient and sleek and new and multi-laned and the fastest way to get from Toronto to London or from Moncton to Halifax. But they are noisy, invasive, monotonous. And ugly.

Driving down a red clay road forces you to drive deliberately and with feeling; encourages you to be aware of where you are and where you’re going. And throws enough randomness and potential for getting lost your way to make life interesting.

Highways force you to drive like an idiot, speeding down endless expanses of gray boredom, anxious, nervous, frustrated, and then suddenly stuck behind a smoke-belching truck for three hours while they clear the five car accident that’s between you and the next off-ramp.

This is all to say that if I was the one on charge of the metaphors, I’d say “information red clay road” is a better metaphor for my take on where all of this internetworking should be taking us than “information highway.”

I’d rather be helping to create pastoral informationscapes than working the tar truck on the infobahn.

I’ve strung out this metaphor so long because it’s useful in explaining three things that I’ve come to think about client/server computing:

First, that we, as knowledge architects, have to start looking at the aesthetics of what it we’re creating. We have to start bringing an overarching design sense to information spaces, looking at broader issues about the role of the tools we are creating in real people’s lives. We have to start using caring, compassion and beauty as design criteria as well as efficiency, throughput and feature-richness. I want us to start worrying about how it feels to use Gopher as well as how its viewers and bookmarks work.

I’m not saying, that we must throw spanners into the works and go back to riding horses so that we can drink in life. But I’m saying that carelessly paving everything in site isn’t necessarily the best approach to creating a better world.

The second thing I think is that we’ve all got to calm down a little. While it’s easy to get caught up in revolutionary fervor, thinking that if we can only get our server to Z39.50 v3 we’ll really have things licked, thinking that being able to, say, look at pictures from the national gallery in Australia in Mosaic or being able to get up-to-the minute weather forecasts from wx.atmos.uiuc.edu, is the precursor to what Andy Bjerring called “a whole new society,” I think it’s important to admit, if only once in a while, that computers are boring, and that people will read the Popular Mechanics magazines in their grandmother’s attic in 50 years and wonder how we could have ever been so caught up.

While I can’t say that I’m displeased with the amount of attention that my little project in PEI has received, at least in that small corner of of the world where crafts and the Internet converge, I don’t really consider us to have done anything all that significant in a larger sense. Craftspeople can now find it somewhat easier to find suppliers. Period. They’ll still go on creating crafts as they have been, the tide will rise and fall every day, and I still like meeting people face to face a lot more than exchanging email.

Finally, and in a way to contradict everything else I’ve just said, I think client/server computing and internetworking in general do have the potential to dramatically change society for the better.

The reason that the Shaw government paved 30 miles of First Kings in 1966 is because they knew that transportation — getting around, and getting around better — is the kind of thing that real people care about. In a place like PEI, where it sometimes seems that somewhere is always very far away, getting around, getting away, even just getting up to Bobby Clow’s store to pick up some molasses so you can make ginger snaps, is a very important issue.

When Keith Rogers started CFCY Radio in Charlottetown in the 1930s, he improved the lives of Islanders, told them more about themselves, gave them local music and news and hockey games from away. When the Island Telephone Company strung lines to New London and set up a phone exchange and hired three operators, it gave the community three information workers who could do anything from calling the volunteer firefighters out of bed to save someone’s barn to keeping track of what the hymns were at church on Sunday or who was sick and who had died and who had just proposed to who.

The sad thing is that now CFCY Radio plays the greatest hits of the 70s, 80s and 90s and might as well be in Red Deer, Alberta as in Charlottetown, and IslandTel is just another boring Stentor lump owned by BCE. The telephone operators are gone and the hits just keep on coming and what we thought, 50 years ago, were going to be the tools that were going change the very fabric of our society have, I think, come up short.

And so now we have another shot at it. We can create a world where geography becomes both more and less important. I can live in Prince Edward Island and wake up every morning and say hello to the cows next door, drive into work in Charlottetown, population 15,000, and have access to the same knowledge tools that anyone else anywhere in the world does. What’s more, and I think what’s more important, is that knowledge can change from being something that flows from the centre — Toronto, New York, Los Angeles — to the periphery — Tignish, Clarenville, Meat Cove. Prince Edward Island craftspeople can shift from feeling as though they are on the fringes of a small Island artistic community to feeling part of a large, global, crafts community. And never leave their cabin in the woods.

Or we can hand over the keys to Stentor and CompuServe and Quicklaw and be content to all tap into the Big Servers in Toronto with our Little Clients everywhere else. We can watch as this anarchic, elegant, decentralized system that we’ve thrown together becomes catalogues and monotonous and centralized and boring. We can watch as software stops getting written because “it would be cool” and starts getting written because it will make NBC and CBS and ABC and Time Warner and Doubleday lots of money as the masses pay to get enfranchised.

We have, in other words, the opportunity to decide whether to pave everything in site or to take a right turn at the Appin Road, drive up the way for a couple of miles until the pavement ends and to slow down and pay attention to life for a change.

I am

I am

Comments

Very interesting talk, Peter.

Very interesting talk, Peter. In the age of Myspace, Facebook and other social media, being able to connect with the world is a blessing and a curse.

Being able to connect with the world is a blessing in that I can find out what’s happening in local, provincial, federal and international politics by reading the Economist, the Globe and Mail, etc. online. I sing in two local choirs - both have web pages, Youtube accounts and Facebook pages. The benefit of all this is that people can find out what the choirs are doing and, if they’re visiting, come hear one of the two choirs if they so choose. I love to read about international musical groups as well.

Being able to connect with the world is also a curse in that there is too much information out there, much of it totally useless. Using the Internet doesn’t require any critical thinking and too many people rely on Wikipedia for important information on history and geography - Wikipedia is user-created and updated and there is no review.

I’d rather talk to people to get my information - if I learn that someone is recently in Canada from Bosnia, Serbia or some other war torn area, I’m more likely to get unbiased views than from a site like Wikipedia.

There is also something to be

There is also something to be said for a technology that allows someone who you used the play with when you were both a year old pop in and leave word from time to time :-)

Great article Peter. I like

Great article Peter. I like to think that like the highway system, there are still requirements for the multi-lane highways and the clay roads on the internet.

I also know from personal experience that the advent of this network has enabled us to be part of the larger community while still enjoying the wonderful life as an Islander.

Thanks for bringing back some memories…

Add new comment